Overview and Epidemiology

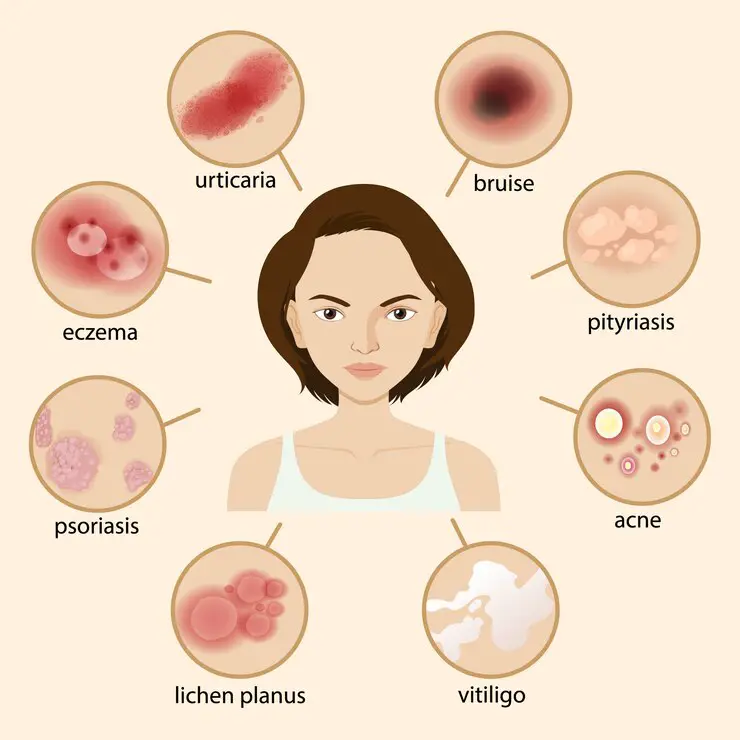

Psoriasis is characterized by accelerated keratinocyte proliferation and chronic inflammation, leading to thickened, scaly skin lesions. There are five principal subtypes, each with distinct clinical presentations:

-

Plaque Psoriasis (psoriasis vulgaris)

-

Guttate Psoriasis

-

Pustular Psoriasis

-

Inverse Psoriasis

-

Erythrodermic Psoriasis

Globally, psoriasis affects an estimated 125 million people. Prevalence varies by geography and ethnicity—ranging from less than 0.5% in some Asian countries to over 3% in Northern Europe and North America. Although it can occur at any age, two peaks in incidence are noted: one in early adulthood (ages 15–30) and another around age 50–60. Men and women are equally affected.

2. Pathophysiology: How Psoriasis Develops

2.1 Immune Dysregulation

At its core, psoriasis is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune condition. In genetically predisposed individuals, environmental triggers activate dendritic cells in the skin, which in turn stimulate naïve T cells to differentiate into Th1, Th17, and Th22 subtypes. These effector T cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines—tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-17 (IL-17), interleukin-23 (IL-23), and interleukin-22 (IL-22)—perpetuating a cycle of inflammation.

2.2 Keratinocyte Hyperproliferation

Under the influence of these cytokines, keratinocytes (the predominant epidermal cells) proliferate at an abnormally rapid rate: in psoriasis, the normal 28-day skin-cell renewal cycle shortens to as few as 3–5 days. This accelerated turnover results in accumulation of incompletely differentiated cells, forming the characteristic silvery scales of psoriatic plaques.

2.3 Genetic Predisposition

More than 60 genetic loci (PSORS1–PSORS9 and other susceptibility regions) have been linked to psoriasis. The HLA-Cw6 allele in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on chromosome 6 is most strongly associated with early-onset plaque psoriasis. Family history is positive in up to 40% of cases.

3. Clinical Subtypes and Their Hallmark Features

3.1 Plaque Psoriasis (Psoriasis Vulgaris)

-

Prevalence: ~80–90% of all psoriasis cases

-

Appearance: Erythematous (red) plaques with well-demarcated borders, covered by thick, silvery-white scales

-

Common Sites: Scalp, elbows, knees, sacral area, and extensor surfaces

-

Symptoms: Itching, burning, and pain; can crack, bleed, or become infected

3.2 Guttate Psoriasis

-

Prevalence: 2–5% of cases; more common in children and young adults

-

Appearance: Numerous small (0.5–1.5 cm), drop-shaped salmon-pink papules with fine scale

-

Trigger: Often follows streptococcal pharyngitis (“strep throat”) by 2–3 weeks

-

Course: Many patients experience spontaneous resolution, though some progress to chronic plaque psoriasis

3.3 Pustular Psoriasis

-

Variants:

-

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis (Von Zumbusch): Widespread sterile pustules on erythematous skin, accompanied by fever and malaise—an emergency.

-

Palmoplantar Pustulosis: Recurrent pustules localized to palms/soles.

-

-

Complications: Electrolyte imbalances, secondary infection

3.4 Inverse (Flexural) Psoriasis

-

Appearance: Smooth, shiny, erythematous plaques without heavy scaling

-

Locations: Skin folds (axillae, groin, under breasts, genitalia, intergluteal cleft)

-

Challenges: Occlusion and friction exacerbate lesions; can be mistaken for fungal or bacterial intertrigo

3.5 Erythrodermic Psoriasis

-

Prevalence: <3% of cases

-

Symptoms: Near-total body erythema and scaling, intense pruritus, pain, and systemic signs (fever, tachycardia)

-

Risk: High risk of dehydration, electrolyte disturbance, and cardiac strain—requires hospitalization

4. Common Triggers and Exacerbating Factors

Although genetic predisposition sets the stage, various environmental and lifestyle factors can provoke or worsen psoriasis flares:

| Trigger | Mechanism/Evidence |

|---|---|

| Infections | Streptococcal throat infections can precipitate guttate psoriasis; HIV and other systemic infections may exacerbate |

| Skin Trauma (Koebner Phenomenon) | Cuts, burns, tattoos, or friction can induce psoriatic lesions at the injury site |

| Medications | Beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials, and NSAIDs have been implicated in triggering or worsening psoriasis |

| Stress | Psychological stress increases circulating cortisol and catecholamines, altering immune responses |

| Alcohol | Excessive intake correlates with higher severity and reduced treatment response |

| Smoking | Tobacco use is associated with increased risk and more severe disease |

| Obesity | Adipose tissue secretes pro-inflammatory adipokines, worsening systemic inflammation |

| Climate | Cold, dry weather can precipitate flares; UV exposure often improves symptoms |

5. Diagnostic Approaches

5.1 Clinical Examination

Diagnosis is primarily based on history and physical findings:

-

Lesion morphology (scaling plaques, pinpoint pustules).

-

Distribution pattern (extensor surfaces, scalp, intertriginous areas).

-

Nail changes: pitting, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis.

-

Family history of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.

5.2 Skin Biopsy

Reserved for atypical or unclear cases. Histopathology confirms:

-

Acanthosis (epidermal hyperplasia)

-

Parakeratosis (retention of nuclei in the stratum corneum)

-

Elongated rete ridges

-

Mixed inflammatory infiltrates in dermis

5.3 Screening for Comorbidities

Patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis warrant evaluation for associated conditions:

-

Psoriatic arthritis (joint pain, stiffness, dactylitis)

-

Metabolic syndrome (central obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance)

-

Cardiovascular disease (hypertension, atherosclerosis)

-

Depression and anxiety

6. Treatment Modalities

While there is no cure, a tiered approach customizes therapy based on disease severity, distribution, patient preference, and comorbidity profile.

6.1 Topical Therapies (Mild Disease)

| Agent | Mechanism | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | Anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative | Varying potency; rotate to minimize tachyphylaxis |

| Vitamin D Analogs | Inhibit keratinocyte proliferation | Calcipotriene, calcitriol |

| Topical Retinoids | Normalize differentiation, reduce inflammation | Tazarotene (avoid during pregnancy) |

| Calcineurin Inhibitors | Block T-cell activation | Tacrolimus, pimecrolimus (particularly for face/folds) |

| Coal Tar Preparations | Anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory | Less commonly used due to odor/staining |

6.2 Phototherapy (Moderate Disease)

-

Narrowband UVB (311 nm): First-line, safe and effective.

-

Broadband UVB: Less used due to higher erythema risk.

-

PUVA (Psoralen + UVA): Reserved for refractory cases; potential long-term carcinogenic risk.

6.3 Systemic Agents (Severe or Extensive Disease)

| Drug Class | Examples | Mechanism / Key Points |

|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate | Methotrexate | Folic acid antagonist; weekly dosing; monitor liver function |

| Cyclosporine | Cyclosporine | Calcineurin inhibitor; rapid onset; nephrotoxicity risk |

| Acitretin | Acitretin | Oral retinoid; teratogenic; mucocutaneous side effects |

| Apremilast | Apremilast | PDE4 inhibitor; oral; mild to moderate efficacy |

| Biologics | TNF-α inhibitors (e.g., etanercept, adalimumab) |

7. When to Consult a Dermatologist

Early referral to a specialist is advised when:

-

Lesions cover >10% body surface area

-

Involvement of face, hands, feet, or genitals impairs function or quality of life

-

Signs of psoriatic arthritis (joint pain, stiffness, swelling)

-

Failure of topical therapies after 2–3 months

-

Severe psychological impact (depression, social withdrawal)

-

Comorbid conditions requiring integrated management

8. Lifestyle Measures and Supportive Care

8.1 Skin-Care Practices

-

Gentle cleansing: Use soap-free or pH-balanced cleansers.

-

Regular moisturization: Thick emollients or ointments to repair barrier function.

-

Bath additives: Colloidal oatmeal or bath oils to soothe itching and scaling.

8.2 Diet and Exercise

-

Anti-inflammatory diet: Emphasize fruits, vegetables, fatty fish, and whole grains.

-

Weight management: Reduces mechanical stress on skin and joints, improves treatment response.

-

Moderate exercise: Lowers systemic inflammation and supports mental well-being.

8.3 Stress Management

-

Mind-body techniques: Meditation, yoga, and biofeedback can decrease flare frequency.

-

Cognitive-behavioral therapy: Addresses the emotional burden of chronic disease.

9. Long-Term Outlook and Comorbidity Management

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disorder with implications extending beyond the skin. Longitudinal studies demonstrate:

-

Increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, driven by chronic inflammation.

-

Higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and diabetes.

-

Elevated risk of depression and suicidal ideation, underscoring the need for integrated psychosocial care.

A multidisciplinary approach—dermatologists, rheumatologists, primary-care physicians, nutritionists, and mental-health professionals—ensures comprehensive management of both cutaneous and extracutaneous aspects.

Conclusion

Psoriasis affects millions worldwide, yet many patients endure delays in diagnosis and suboptimal treatment. By recognizing the hallmark symptoms—red, scaly plaques; drop-shaped lesions; sterile pustules; or widespread erythroderma—individuals and clinicians can initiate timely evaluation. Understanding the underlying immune dysregulation, genetic predisposition, and environmental triggers lays the foundation for personalized therapy.

While no cure exists, the expanding arsenal of topical agents, phototherapy protocols, systemic medications, and biologic therapies offers hope for sustained remission and improved quality of life. Coupled with lifestyle modifications, stress reduction, and vigilant screening for comorbidities, patients with psoriasis can achieve meaningful disease control and lead full, active lives.

If you suspect psoriasis—persistent, itchy, or painful skin changes—it is imperative to consult a healthcare provider. Early intervention not only alleviates symptoms but also mitigates long-term risks associated with this chronic inflammatory condition. Empower yourself with knowledge, seek professional guidance, and partner with your medical team to manage psoriasis effectively. Your skin—and your overall health—depend on it.

Adrian Hawthorne is a celebrated author and dedicated archivist who finds inspiration in the hidden stories of the past. Educated at Oxford, he now works at the National Archives, where preserving history fuels his evocative writing. Balancing archival precision with creative storytelling, Adrian founded the Hawthorne Institute of Literary Arts to mentor emerging writers and honor the timeless art of narrative.