The morning fog hung low over Riverside County as Sergeant Alexander Vance wheeled his chair through the courthouse parking lot, the familiar weight of dread settling in his chest. At thirty-four, he had faced enemy fire in Fallujah, survived three tours of duty, and endured countless surgeries to save what remained of his shattered legs. Yet nothing had prepared him for the particular kind of battle he was about to fight in Courtroom Seven—a battle against a system that seemed determined to treat him as a problem rather than a person.

Alexander’s story began not in this courthouse, but on a dusty road outside Baghdad five years earlier. Sergeant First Class Alexander Vance had been leading a convoy escort mission when the improvised explosive device detonated beneath his Humvee. The blast had been so powerful that it lifted the three-ton vehicle completely off the ground, flipping it twice before it came to rest in a smoking heap of twisted metal and shattered dreams. His two squad members died instantly. Alexander survived, but at a cost that would define the rest of his life.

The months that followed were a blur of military hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and adaptive equipment training. The Army doctors had been direct in their assessment: extensive nerve damage, severed spinal connections, and muscle destruction that no amount of physical therapy could fully repair. His legs, once strong enough to carry a full combat load across miles of desert terrain, would never again support his weight. The wheelchair wasn’t temporary—it was permanent, a daily reminder of the moment his life had changed forever.

But Alexander had refused to let his injury define his worth. After his medical discharge, he had returned to Riverside County with a fierce determination to rebuild his life on his own terms. He enrolled in community college using his GI Bill benefits, studying business administration with dreams of opening a nonprofit to help other disabled veterans navigate the bureaucratic maze of veteran services. He volunteered at the local VA hospital, sharing his experience with newly injured soldiers who were beginning their own journeys toward acceptance and adaptation.

It was this commitment to helping others that had indirectly led to his current legal troubles. Alexander had been scheduled to appear in court six months earlier as a witness in a personal injury case involving another veteran. The case involved Michael Torres, a young Marine who had lost his right arm to an IED and was seeking compensation from a contractor whose faulty equipment had contributed to his injury. Alexander’s testimony about the psychological impact of combat injuries was considered crucial to establishing the full scope of Michael’s damages.

When Alexander had arrived at the courthouse that day, he discovered what should have been obvious to anyone with basic knowledge of accessibility requirements: the building’s main elevator was broken, and had been for weeks. The backup elevator was located in a section of the building that was closed for renovations. The only way to reach the second-floor courtroom was via a narrow staircase that might as well have been Mount Everest for someone in a wheelchair.

The bailiff who met him at the entrance had been apologetic but firm. “I’m sorry, sir, but there’s no way to get you upstairs today. You’ll need to reschedule.”

“This case has already been delayed twice,” Alexander had explained patiently. “Mr. Torres is counting on my testimony. Isn’t there any alternative?”

The bailiff had shrugged helplessly. “You could try calling the clerk’s office to request a venue change, but that would probably delay things another few months.”

Alexander had spent the next three hours on his phone, calling every number he could find, speaking to clerks, administrators, and eventually a judge’s assistant who seemed genuinely sympathetic to his situation. The assistant had promised to “look into options” and “get back to him as soon as possible.” That call never came.

When Alexander failed to appear for his scheduled testimony, the court had issued a bench warrant for contempt. He had tried to explain the situation through his attorney, submitted written statements documenting the accessibility issues, and even provided photographs of the broken elevator and inaccessible staircase. Each attempt at communication had been met with bureaucratic indifference or, worse, subtle suggestions that he was making excuses for his “failure to appear.”

The contempt charges had escalated over the following months as Alexander continued to miss court dates, not out of defiance or disrespect, but because the courthouse remained physically inaccessible to him. His written requests for reasonable accommodations—video testimony, a temporary courtroom on the ground floor, or even just confirmation that the elevator would be working on his scheduled appearance date—had been denied, ignored, or lost in the administrative shuffle.

His attorney, David Martinez, was a recent law school graduate working for a nonprofit legal aid organization. Well-meaning but inexperienced, David had struggled to navigate the complex intersection of disability rights law and court procedures. His motions had been technically correct but lacked the persuasive force needed to break through decades of institutional inertia. The court system, designed for able-bodied participants, seemed incapable of recognizing that accessibility wasn’t a special favor—it was a legal requirement and a moral imperative.

As the charges had mounted, Alexander found himself caught in an impossible situation. His failure to appear was being treated as willful contempt, punishable by fines he couldn’t afford and potential jail time that would devastate his fragile financial stability. The irony wasn’t lost on him: he was being punished for his inability to access a building that was legally required to accommodate his disability.

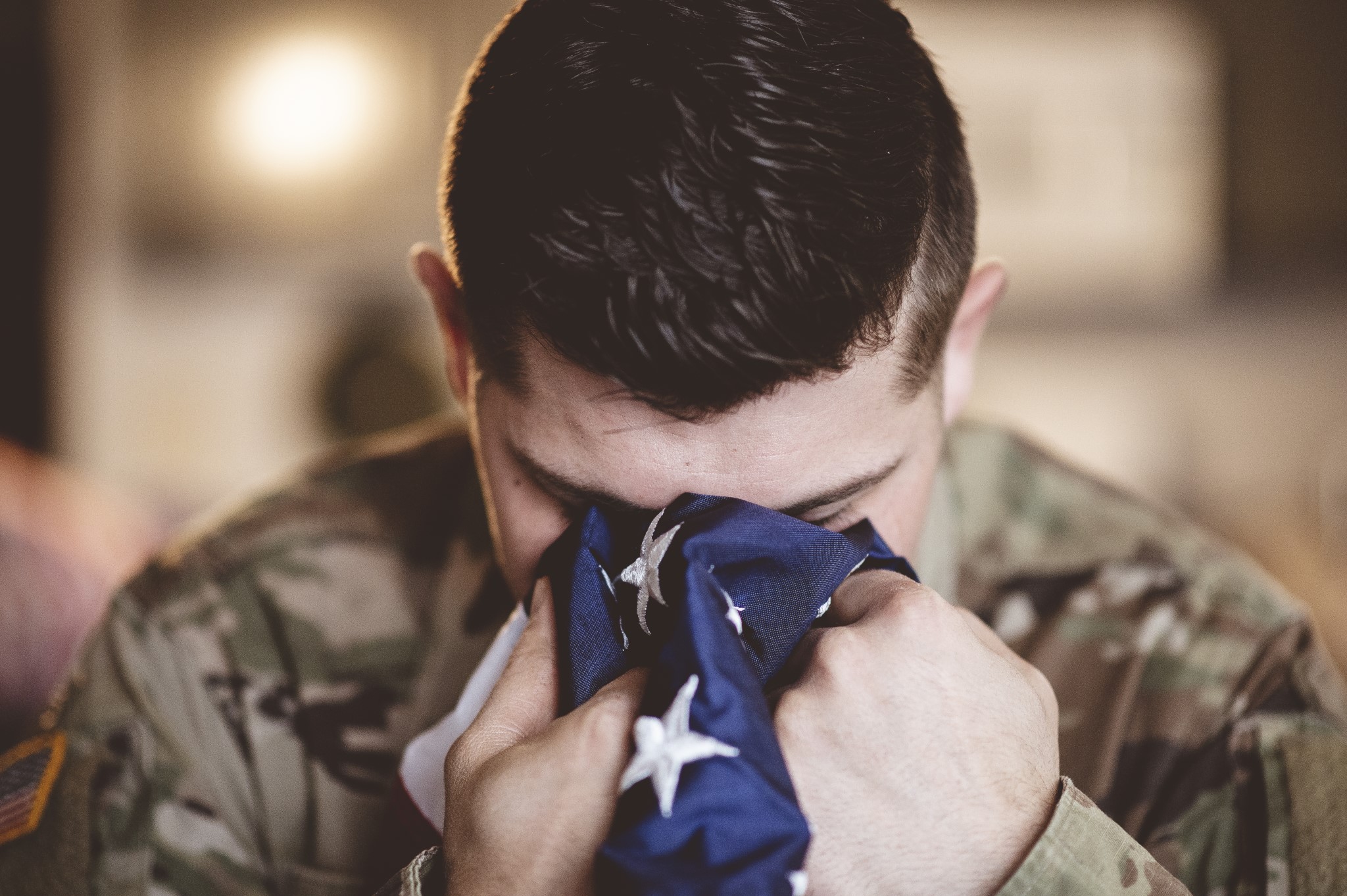

The night before his final court date, Alexander had sat in his small apartment, staring at the Purple Heart and Bronze Star displayed on his kitchen wall. These medals represented moments when he had risked everything for his country, when he had put the lives of his fellow soldiers above his own safety and comfort. Now, that same country seemed determined to treat him as a second-class citizen whose needs were an inconvenience to be ignored.

His younger sister, Maria, had called that evening from her home in Phoenix. She was a nurse, practical and compassionate, and she had been following his legal troubles with growing anger.

“Alex, this is insane,” she had said, her voice tight with frustration. “You literally can’t get into the building. How is that your fault?”

“The judge doesn’t see it that way,” Alexander had replied wearily. “According to the court, I’m just another defendant making excuses.”

“Have you considered going to the media? This is exactly the kind of story that gets attention. A disabled veteran being punished for the courthouse’s failure to provide basic accessibility?”

Alexander had considered that option, but something in him rebelled against the idea of using his military service as leverage for sympathy. He had never wanted to be seen as a victim, never wanted his injuries to become a tool for manipulation or public relations. He was proud of his service, but he was more than his disabilities, more than his war wounds, more than the sum of what he had lost.

“I just want to be treated fairly,” he had told Maria. “I don’t want special treatment because I’m a veteran. I just want the same access to justice that every other citizen has.”

The morning of his court appearance, Alexander had arrived at the courthouse to find that the elevator was indeed working—a small miracle that had taken six months to achieve. As he rode up to the second floor, he felt a mixture of relief and bitter irony. The very accommodation he had been requesting for months was now available, but only after he had been branded a criminal for its absence.

Courtroom Seven was a traditional judicial chamber, all dark wood paneling and formal furnishings designed to inspire respect for the majesty of the law. High ceilings and tall windows gave the space an almost cathedral-like atmosphere, while the raised judge’s bench reinforced the hierarchical nature of the proceedings. It was the kind of room where justice was supposed to be blind, impartial, and fair—qualities that had seemed notably absent from Alexander’s experience with the system.

Judge Evelyn Hayes had been on the bench for fifteen years, building a reputation as a no-nonsense jurist who valued order and efficiency above all else. She had earned her position through decades of prosecutorial work, winning convictions through meticulous preparation and unwavering adherence to legal procedure. Her courtroom ran like clockwork, with strict rules about everything from dress code to speaking protocols. She was respected by attorneys for her legal knowledge and feared for her intolerance of anything that disrupted her carefully managed proceedings.

At sixty-two, Judge Hayes had seen thousands of defendants pass through her courtroom. She had heard every excuse, every sob story, every creative explanation for why someone had failed to follow court orders. In her experience, showing flexibility or sympathy only encouraged more of the behavior she was trying to discourage. Rules existed for a reason, and exceptions were dangerous precedents that could undermine the entire system.

But Judge Hayes had never served in the military. She had never been injured in service to her country. She had never faced the daily challenges of navigating a world designed for people whose bodies worked differently than hers. Her perspective on Alexander’s case was filtered through decades of legal training that emphasized compliance over compassion, procedure over humanity.

As the morning session began, the courtroom filled with the usual mix of attorneys, defendants, and court personnel. Most were there for routine matters—traffic violations, small claims disputes, and minor criminal charges that formed the bulk of the county court system’s daily business. Few of the spectators paid much attention to the man in the wheelchair who positioned himself at the defendant’s table, his Purple Heart pin barely visible on his jacket lapel.

Alexander’s attorney, David Martinez, made one final attempt to address the accessibility issues that had led to his client’s contempt charges. Standing nervously before the bench, the young lawyer presented a carefully prepared argument about the Americans with Disabilities Act, the courthouse’s obligation to provide reasonable accommodations, and the fundamental unfairness of punishing someone for the system’s own failures.

“Your Honor,” David began, his voice carrying the earnestness of someone who genuinely believed in the justice system’s capacity for fairness, “my client’s failure to appear was not willful contempt but rather the direct result of the courthouse’s inability to provide legally required accessibility accommodations. Sergeant Vance served three tours of duty in Iraq and sustained injuries that left him permanently wheelchair-bound. He has attempted repeatedly to work with the court to find solutions that would allow him to fulfill his legal obligations while accommodating his disabilities.”

Judge Hayes listened with the polite attention she gave to all legal arguments, but her expression remained unchanged. She had reviewed the case file that morning, noting the multiple missed court dates and the various explanations offered for each absence. In her view, this was a clear-cut matter of contempt, complicated only by the defendant’s attempt to use his military service and disability as excuses for noncompliance.

“Mr. Martinez,” she interrupted, “your client had multiple opportunities to appear before this court. The fact that he chose not to avail himself of alternative arrangements does not excuse his contempt. This court cannot function if defendants are allowed to ignore lawful orders based on their personal circumstances.”

David tried to continue his argument, explaining the specific barriers his client had faced, but Judge Hayes had already made up her mind. She had a docket to clear, precedents to maintain, and no patience for what she saw as elaborate justifications for simple noncompliance.

“The defendant will stand for sentencing,” she announced, her voice carrying the absolute authority of fifteen years on the bench.

The words hit the courtroom like a physical blow. Every person present understood the impossibility of what had just been demanded. Alexander sat motionless in his wheelchair, his hands resting on the armrests, his face a mask of controlled dignity. He had faced enemy fire without flinching, had endured surgery after surgery without complaint, had rebuilt his entire life from the ground up without asking for pity. But this moment—this casual, thoughtless command—threatened to break something fundamental inside him.

The silence that followed was profound and uncomfortable. Court reporters stopped typing. Bailiffs shifted nervously. Even the most routine courthouse personnel seemed to recognize that they were witnessing something extraordinary—not the usual drama of legal proceedings, but a collision between institutional inflexibility and human dignity that would leave everyone changed.

David Martinez started to object, his voice rising in protest at the obvious impossibility of his client’s situation. But Alexander raised one hand slightly, a gesture so subtle it was almost missed, yet commanding enough to silence his attorney immediately. This was his moment, his choice, his response to a system that had failed him at every turn.

What happened next would be remembered by everyone present for the rest of their lives.

Alexander gripped the armrests of his wheelchair with both hands, his knuckles whitening as he attempted to push himself upward. The effort was immediately visible in every line of his body—the corded muscles of his neck standing out as he strained, his face flushing with exertion, his breathing becoming labored and harsh. The courtroom watched in stunned silence as he fought against the limitations his injuries had imposed, driven by a determination that transcended physical possibility.

Inch by painful inch, Alexander managed to lift his body slightly from the wheelchair seat. His arms trembled with the effort, his damaged legs hanging uselessly as he supported his entire weight through upper body strength alone. Sweat beaded on his forehead as he held the position for several seconds, his body shaking from the strain of defying both gravity and his own physical limitations.

The sight was both inspiring and heartbreaking—a man who had already given so much, now forced to prove his respect for a system that had shown him none in return. Every person in the courtroom could see the cost of this simple act, the physical pain and emotional humiliation of being required to perform an impossibility for the sake of legal protocol.

When his strength finally gave out, Alexander’s collapse back into his wheelchair echoed through the silent courtroom like a judgment of its own. The impact seemed to reverberate not just physically, but morally, challenging everyone present to consider what they had just witnessed and what it said about their own values and priorities.

It was then that something remarkable happened—something that would transform not just this court proceeding, but the lives of everyone who witnessed it.

A man in the gallery, someone Alexander had never met, rose slowly to his feet. He was middle-aged, wearing a simple business suit, his face reflecting the same mixture of emotion that had gripped everyone in the room. His standing seemed to say what words could not: that if this veteran could not stand, then others would stand for him.

The gesture was immediately understood and embraced by everyone present. One by one, without coordination or instruction, every person in the courtroom rose to their feet. Attorneys stood behind their tables. Court clerks rose from their desks. Bailiffs straightened to attention. Spectators in the gallery stood as one, their faces reflecting a mixture of respect, shame, and determination.

Within moments, the entire courtroom was standing in silent tribute to a man whose courage had just been tested in the most fundamental way possible. They stood for the service he had rendered to his country. They stood for the sacrifices he had made on behalf of people he had never met. They stood for the dignity he had maintained despite being failed by the very system he had sworn to protect.

But most importantly, they stood because they recognized that in this moment, they were witnessing something that transcended legal procedures and courtroom protocols. They were seeing the difference between law and justice, between following rules and doing what was right.

Judge Hayes, who had spent fifteen years maintaining strict control over her courtroom, found herself facing something entirely outside her experience. The authority she had wielded so confidently moments before seemed suddenly hollow and irrelevant in the face of this collective moral statement. Her gavel, the symbol of her power to enforce order and compliance, lay silent on her bench as she confronted the inadequacy of legal procedure to address fundamental questions of human dignity.

For the first time in her judicial career, Judge Hayes felt the weight of a decision that extended far beyond the narrow confines of contempt proceedings. She was being asked to choose between institutional inflexibility and human compassion, between the letter of the law and the spirit of justice that the law was supposed to serve.

Looking out over her courtroom, filled with people standing in silent solidarity with a veteran who had already paid more than his share for the freedoms they all enjoyed, Judge Hayes felt something crack in the rigid framework of her professional worldview. The tears that began to form in her eyes were not just for this one moment, but for all the moments when she had chosen procedure over humanity, when she had let the machinery of justice grind forward without considering the human cost of its operation.

Her voice, when she finally spoke, was barely above a whisper. “Sergeant Vance,” she said, the title carrying a weight and respect that had been absent from her earlier pronouncements. “This court owes you not just an apology, but a debt of gratitude that can never be fully repaid.”

The admission seemed to cost her physically, as if acknowledging her mistake required her to confront fifteen years of similar failures to see the human beings behind the case numbers. “The charges against you are dismissed,” she continued, her voice growing stronger as she found her footing in this new moral territory. “And this court will ensure that the accessibility issues that led to this situation are immediately and permanently addressed.”

The gavel’s fall was gentle this time, not the sharp crack of legal authority but the soft acknowledgment of a lesson learned. The sound seemed to release something in the courtroom, and what followed was not applause but something deeper—tears, quiet sobs, and the kind of emotional release that comes when people witness justice finally being served.

Alexander lowered his head, not in defeat but in gratitude for this unexpected validation of his dignity and worth. For months, he had felt like he was fighting this battle alone, pushing against a system that seemed designed to exclude and diminish him. Now, surrounded by the solidarity of strangers who had recognized his humanity when the system had failed to do so, he felt the burden of isolation finally beginning to lift.

As people began to file out of Courtroom Seven, they carried with them the memory of what they had witnessed—a moment when ordinary people had chosen to stand up for what was right, even when doing so challenged the established order. They had seen the power of collective action to transform individual suffering into community healing, and many would carry that lesson forward into their own lives and communities.

David Martinez, the young attorney who had struggled to find the right legal arguments to protect his client, realized that he had just witnessed something that no law school could teach—the moment when justice transcends legal procedure and becomes a expression of shared humanity. The experience would shape his entire career, leading him to specialize in disability rights law and ensuring that other veterans like Alexander would never face the same barriers to justice.

Judge Hayes, meanwhile, faced the difficult task of reconciling her new understanding with fifteen years of judicial practice. That afternoon, she called an emergency meeting with court administrators to address the accessibility issues that had led to this crisis. She ordered immediate repairs to the elevator system, established protocols for ensuring disabled access to all court proceedings, and implemented training programs to help court personnel better serve citizens with disabilities.

But her transformation went deeper than procedural changes. She began to review her previous cases, looking for other instances where her rigid adherence to rules might have caused unnecessary hardship or injustice. She started visiting veterans’ organizations and disability advocacy groups, not as a judge but as someone seeking to understand the daily challenges faced by people whose experiences differed from her own.

The story of what happened in Courtroom Seven that day spread quickly through the veteran community and beyond. Media outlets picked up the story, but rather than focusing on the controversy or conflict, most coverage emphasized the positive outcome and the lesson it offered about the power of collective action to support justice.

Alexander found himself reluctantly thrust into the spotlight as a symbol of both the challenges faced by disabled veterans and the potential for positive change when communities come together to support their most vulnerable members. He used this unexpected platform to advocate for improved accessibility not just in courthouses, but in all public buildings and services.

Six months later, Alexander was invited to speak at a national conference on veterans’ affairs, sharing his story not as a victim but as an advocate for systemic change. Standing behind a podium—something he could do for short periods with the aid of leg braces and determination—he spoke about the importance of treating veterans not as heroes to be pitied but as citizens deserving of equal access to all the rights and opportunities their service had helped to protect.

“I didn’t serve my country so that I could be given special treatment,” he told the audience of veterans’ advocates, legal professionals, and government officials. “I served so that all Americans could have equal access to justice, equal opportunity for success, and equal dignity under the law. When any citizen is denied those things because of disability, age, race, or any other factor beyond their control, then we have failed to honor the principles we claim to defend.”

The courthouse in Riverside County became a model for accessibility compliance, with representatives from other judicial districts visiting to learn how to better serve citizens with disabilities. Judge Hayes was invited to speak at judicial conferences about the importance of looking beyond legal procedure to ensure that justice was truly accessible to all.

Alexander completed his business degree and successfully launched his nonprofit organization, which he named “Stand Together Veterans Services.” The organization helps disabled veterans navigate bureaucratic systems, provides advocacy services for those facing legal challenges related to their disabilities, and works to improve accessibility in public buildings and services throughout the region.

On the first anniversary of his court appearance, Alexander returned to Courtroom Seven—not as a defendant, but as an invited speaker at a ceremony launching the courthouse’s new accessibility initiative. Judge Hayes introduced him, speaking about the lessons she had learned and the changes that had been implemented as a result of their encounter.

“A year ago, this courtroom was the site of a profound failure of justice,” she told the assembled crowd of veterans, disability advocates, and court personnel. “But it also became the site of a powerful demonstration of the values that make our justice system worth preserving and improving. Sergeant Vance reminded us that law without compassion is merely tyranny, and that true justice requires us to ensure equal access for all citizens.”

Alexander’s speech that day was brief but powerful. He spoke about forgiveness, about the importance of learning from failures, and about the collective responsibility to ensure that the rights and dignity of all citizens are protected and preserved. But perhaps most importantly, he spoke about hope—hope that systems can change, that people can grow, and that communities can come together to support their most vulnerable members.

As the ceremony concluded and people began to leave the courthouse, many stopped to shake Alexander’s hand or share their own stories of challenges overcome and communities supporting those in need. The courthouse that had once been a barrier had become a symbol of possibility, proving that even the most entrenched systems can be transformed when people of good will commit to doing what is right.

The changes that began in Courtroom Seven that day extended far beyond accessibility improvements or legal procedures. They represented a fundamental shift in understanding about what justice truly means—not just the mechanical application of rules and procedures, but the active commitment to ensuring that all citizens have equal access to the rights and opportunities that democracy promises.

Years later, when people remember the story of Sergeant Alexander Vance and the day an entire courtroom stood up for justice, they remember not just the moment of crisis but the transformation that followed. They remember that change is possible when individuals have the courage to demand better, when communities choose solidarity over indifference, and when institutions commit to serving the people they were created to protect.

Alexander continues to serve his community, not as a soldier carrying a weapon, but as an advocate carrying the hope that justice can be more than just a word carved in stone above courthouse doors. His wheelchair no longer represents what he has lost, but what he continues to give—proof that true service doesn’t end when the uniform comes off, and that the greatest victories are often won not on battlefields, but in courtrooms, community centers, and anywhere people gather to demand that the promise of equal justice under law becomes reality for all.

In the end, the story of Courtroom Seven is not really about accessibility or legal procedure or even military service. It’s about the moment when ordinary people chose to stand up for something greater than themselves, transforming individual suffering into collective action and proving that justice is not just something that happens to us, but something we create together through our choices, our courage, and our commitment to treating every person with the dignity they deserve.

Adrian Hawthorne is a celebrated author and dedicated archivist who finds inspiration in the hidden stories of the past. Educated at Oxford, he now works at the National Archives, where preserving history fuels his evocative writing. Balancing archival precision with creative storytelling, Adrian founded the Hawthorne Institute of Literary Arts to mentor emerging writers and honor the timeless art of narrative.