The Locked Door

An Original Story

My name is Sarah Mitchell, and I need to tell you about the worst mistake of my life. Not because I want sympathy—I don’t deserve it—but because maybe, just maybe, my story will stop someone else from making the same horrifying choice I did.

It started small, the way most terrible things do. A single moment of embarrassment that metastasized into something monstrous.

My son, Oliver, was three years old—a beautiful, energetic little boy with his father’s dark curls and my green eyes. He was curious about everything, always asking questions, always wanting to help, always eager to be part of whatever was happening around him.

We lived in a modest but well-kept house in a suburb of Minneapolis. After my divorce two years earlier, I’d worked hard to build a new life for us. I had a good job as a marketing consultant, nice furniture, a circle of friends who seemed impressed by how well I was “holding it together” as a single mother.

Image mattered to me. It always had, even before the divorce. Growing up, my own mother had been obsessed with appearances—what the neighbors thought, what our relatives would say, whether our house looked impressive enough. I’d internalized those values without even realizing it, measuring my worth by external validation rather than internal peace.

The incident that changed everything happened on a Saturday afternoon in early October. I’d invited some colleagues over for brunch—an attempt to network and socialize, to prove I could manage both motherhood and a professional life without breaking a sweat.

Oliver had been excited about the guests. He’d helped me set the table that morning, carefully placing napkins beside each plate with the intense concentration only a three-year-old can muster. He’d asked if he could show them his new dinosaur book, if he could help pass out the croissants, if they would want to see the tower he’d built with his blocks.

I’d said yes to everything, distracted by preparations, not really thinking through the implications of having an energetic toddler around adults trying to have sophisticated conversations.

The guests arrived—two colleagues from work, Jennifer and Mark, plus Jennifer’s husband, David. They were the kind of people who intimidated me slightly: well-traveled, well-read, always dropping references to restaurants and cultural events I couldn’t quite afford. David, in particular, had an air of refined taste that made me hyperconscious of every detail in my home.

Everything was going well for the first hour. The food was good, the conversation was flowing, and Oliver was being relatively quiet, playing with his toys in the corner of the living room.

Then it happened.

Oliver, trying to be helpful, picked up the pitcher of orange juice to refill David’s glass. It was far too heavy for his small hands. Before I could react, the entire pitcher tipped, sending a cascade of orange juice across the table and directly onto David’s shoes—expensive Italian leather loafers that probably cost more than my monthly grocery budget.

The silence that followed was excruciating.

David jumped up, his face contorted with shock and irritation. “These are Ferragamo!” he said, staring at his juice-soaked shoes. “Do you have any idea how much these cost?”

Oliver’s face crumpled immediately. “I’m sorry,” he whispered, his voice small and terrified. “I was trying to help.”

I rushed to grab towels, apologizing profusely, my face burning with humiliation. Jennifer and Mark exchanged glances—the kind of looks that said they were already composing the story they’d tell other colleagues about Sarah’s chaotic home life.

“It’s fine,” David said, though his tone suggested it was anything but fine. “They’re just shoes. But maybe next time, keep better control of the situation.”

Keep better control of the situation. The words echoed in my mind long after they left, earlier than planned, with promises to “do this again sometime” that we all knew were empty.

After they left, I cleaned up in furious silence while Oliver sat on the couch, clutching his stuffed bear, his eyes red from crying. He kept apologizing, over and over, until I finally snapped at him to stop.

“It was an accident, Oliver. But you need to understand that when adults are talking, you can’t just interrupt and try to do things you’re not big enough to handle.”

He nodded, his lower lip trembling, and something in me hardened. This was the problem, I told myself. This was why single mothers were seen as less capable, less put-together. Because children were unpredictable, embarrassing, disruptive to the careful image I was trying to project.

That night, lying in bed, I made a decision. The next time I had guests over, I would make sure nothing could go wrong. I would make sure Oliver couldn’t accidentally ruin another social occasion.

I told myself it was just practical. Just temporary. Just until he was old enough to behave appropriately around company.

I told myself a lot of lies.

The next time I hosted guests—a book club meeting three weeks later—I implemented my new plan.

An hour before they arrived, I called Oliver into his bedroom. It was a cheerful room, painted soft blue, filled with toys and books. His bed was shaped like a race car, a gift from his grandparents. On the wall were stickers of dinosaurs and spaceships that we’d applied together.

“Oliver, sweetie, Mommy is going to have some friends over tonight. I need you to stay in your room and play quietly while they’re here, okay?”

His face fell immediately. “But I want to see your friends. I’ll be good. I promise I won’t spill anything.”

“I know you’ll try to be good,” I said, my voice taking on a firm edge. “But it’s easier if you just stay in here. You have all your toys. You can play with whatever you want. It’s like a special play time just for you.”

“But—”

“Oliver, this isn’t a discussion. Mommy needs you to cooperate.”

I saw the hurt in his eyes, but I pushed it away. This was necessary, I told myself. This was being a responsible parent—managing situations before they became problems.

I left his room, closed the door, and—for the first time—turned the key in the lock.

The click of that lock is a sound that will haunt me for the rest of my life.

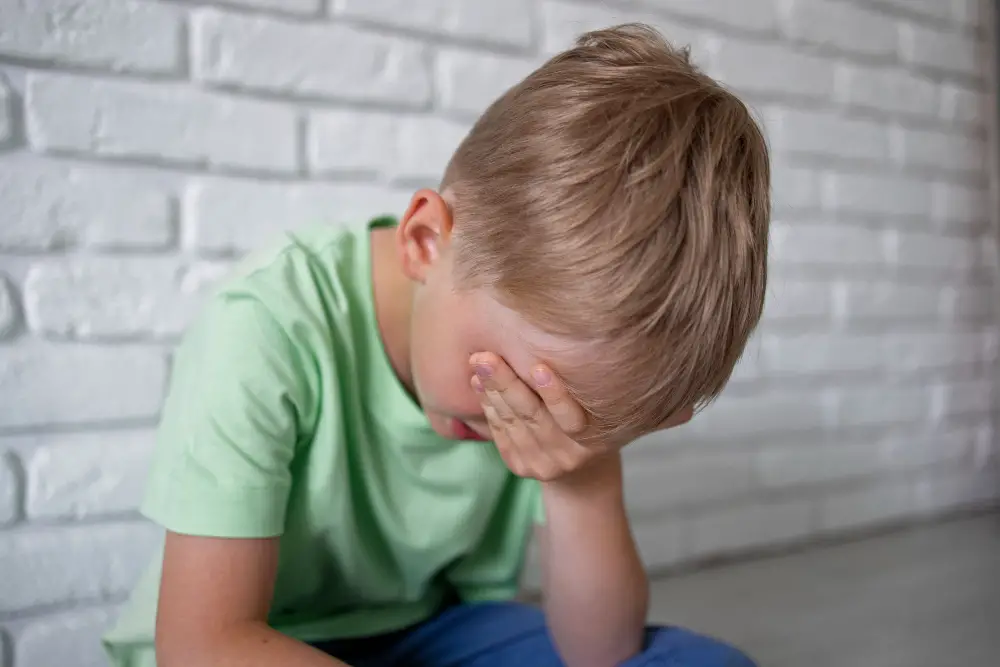

Oliver didn’t cry or scream. He didn’t pound on the door or throw a tantrum. He just called out, once, in a small voice: “Mommy? Mommy, it’s locked.”

“It’s okay, honey. I’ll come get you when my friends leave. Just play with your toys.”

The book club meeting went perfectly. We discussed the novel, drank wine, ate the cheese and crackers I’d arranged on a beautiful platter. No one asked about Oliver. I’d mentioned casually that he was at his grandmother’s for the evening, and no one questioned it.

When the last guest left around ten p.m., I unlocked Oliver’s door to find him asleep on the floor, curled up with his stuffed bear, his face tear-stained. A wave of guilt washed over me, but I pushed it down. He was fine. He’d fallen asleep. No harm done.

This became my pattern over the following months.

Every time I had guests—which became more frequent as I tried to build my social and professional network—Oliver was locked in his room. Sometimes for two hours, sometimes for three or four. I always made sure he had snacks and water beforehand, told him to be quiet, and then locked that door.

The lies I told became more elaborate. He was at daycare extended hours. He was having a sleepover at his grandmother’s (though my mother lived three states away and we rarely saw her). He was at a playdate with a friend from preschool.

Oliver stopped asking to meet my guests. He stopped protesting when I told him it was time to go to his room. He just nodded, gathered his favorite toys, and walked to his bedroom with the resignation of someone far older than three years old.

Sometimes, in the quiet moments between my guests’ laughter and conversation, I’d hear small sounds from down the hall—the soft thump of a toy being moved, the quiet rustle of pages as he looked at his picture books. Once, I heard him singing to himself, so softly I could barely make out the tune.

But mostly, he was silent. Perfectly, eerily silent.

My friends complimented me constantly on how well I was managing single motherhood. “You always look so put together,” Jennifer said at one gathering. “How do you do it all?”

I smiled and deflected, never mentioning the small boy locked in a room down the hall, waiting for his mother to remember he existed.

The truth is, I’d stopped seeing it as wrong. In my mind, I’d constructed a narrative where I was being a good mother—providing a stable home, building a professional network, creating the kind of life where Oliver would have opportunities. The locked door was just… logistics. Management. A temporary solution until he was old enough to understand social norms.

I’d convinced myself that he was fine. Happy, even. He had his toys, his books, his little world. What more could a three-year-old need?

I was about to find out exactly what he needed, and the answer would destroy me.

It was a Friday evening in late January when everything fell apart. I’d planned a small dinner party—just four guests, including a potential client I was trying to impress. I’d spent all day preparing: cleaning the house until it gleamed, cooking an elaborate meal, setting the table with the good dishes I rarely used.

Oliver had been unusually quiet that day. He’d seemed tired at breakfast, pushing his cereal around his bowl without eating much. When I asked if he felt okay, he just nodded and said his tummy hurt a little.

“Probably just growing pains,” I’d said dismissively, not wanting to deal with a potential illness when I had so much to do. “Why don’t you rest on the couch while Mommy gets things ready?”

He’d curled up on the couch with his bear, watching cartoons while I worked around him. Every so often, I’d glance over and see him rubbing his stomach, but he never complained. He’d learned not to complain.

At five p.m., I called him into his room. The routine was so established by now that it required few words.

“Guests are coming in an hour, Oliver. Time to go to your room.”

He stood up slowly, clutching his bear, and walked down the hall. I noticed he was moving more carefully than usual, but I attributed it to tiredness.

“Do you need anything before I lock the door? Water? Snacks?”

He shook his head. “My tummy still hurts, Mommy.”

“You’ll feel better after you rest. Just lie down for a while.”

I kissed his forehead—one small gesture of affection to assuage the guilt I wouldn’t fully acknowledge—and closed the door. The lock clicked into place.

The dinner party was perfect. The food was delicious, the conversation was engaging, and the potential client seemed genuinely impressed by my home and my hosting skills. We laughed, we talked business, we made plans for future collaboration.

Around nine p.m., as dessert was being served, I heard a sound from down the hall. It was faint—a soft thump, followed by what might have been a whimper.

I froze, fork halfway to my mouth.

“Everything okay?” Mark asked, noticing my expression.

“Fine,” I said quickly. “Just thought I heard something. Probably a neighbor.”

But the sound came again. Definitely from Oliver’s room. A soft cry, barely audible over the dinner conversation.

My stomach twisted with unease, but I forced a smile and continued the conversation. He was probably just having a nightmare, I told myself. He’d be fine. The guests would leave soon, and then I’d check on him.

Except the sounds didn’t stop. They became more frequent—small, pained noises that cut through my forced cheer like a knife.

“Sarah, are you sure everything’s alright?” Jennifer asked, concerned. “You seem distracted.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, setting down my fork. “I just need to check something quickly. Please, continue without me.”

I walked down the hall, my heels clicking on the hardwood floor, my heart pounding with a fear I couldn’t quite name. I told myself I was overreacting. Oliver was fine. He was always fine.

I unlocked the door and pushed it open.

The scream that tore from my throat brought all four guests running down the hall.

Oliver was lying on the floor, his face pale and contorted with pain, his body curled into a tight ball. His lips had a bluish tinge, and he was barely conscious, whimpering softly. Next to him was an overturned plastic bottle—the bright blue cleaner I used for the bathroom, stored on a high shelf that he must have climbed to reach.

The cap was off. The bottle was nearly empty.

“OH GOD! OLIVER!” I dropped to my knees beside him, my hands shaking as I tried to pick him up. His body was limp, his breathing shallow and labored.

Behind me, I heard Jennifer’s shocked gasp. “Sarah, is that… is that your son? What is he doing locked in here?”

But I couldn’t answer. I couldn’t do anything except scream for someone to call 911 while I held my dying child in my arms, finally understanding the full horror of what I’d done.

The ambulance arrived within minutes, though it felt like hours. The paramedics worked with frightening efficiency, asking rapid-fire questions I could barely answer through my panic.

“What did he ingest?”

“How long ago?”

“How long was he alone?”

I showed them the bottle. Bathroom cleaner. Highly toxic. Potentially fatal.

They inserted an IV, put an oxygen mask over his small face, and loaded him onto a stretcher. I rode in the ambulance, holding Oliver’s tiny hand, watching the paramedics work to keep him alive.

“Is he going to be okay?” I kept asking, over and over. “Please, tell me he’s going to be okay.”

“We’re doing everything we can, ma’am. The next few hours are critical.”

At the hospital, they rushed him into emergency treatment. A doctor explained that bathroom cleaners contain chemicals that can cause severe internal burns, damage to the esophagus and stomach, respiratory distress, and potential organ failure.

“We need to act fast,” she said. “He’s already showing signs of chemical burns in his throat and esophagus. We’re going to pump his stomach, give him activated charcoal, and monitor his vital signs closely.”

“Will he survive?” My voice was barely a whisper.

The doctor’s expression was professionally neutral, but I saw the concern in her eyes. “I can’t make any promises. The next twelve to twenty-four hours will tell us a lot. But Ms. Mitchell, I need to ask you some questions about how this happened.”

That’s when I realized I’d have to explain. I’d have to tell them that my three-year-old son had been locked in his room, thirsty and scared, and had drunk bathroom cleaner because he thought it might be juice.

I’d have to tell them what kind of mother I was.

A nurse led me to a small consultation room while they worked on Oliver. A social worker arrived within the hour—a middle-aged woman named Patricia Rodriguez with kind eyes and a clipboard.

“Ms. Mitchell, I need you to walk me through exactly what happened tonight.”

I told her everything. The locked door. The dinner party. Finding Oliver on the floor. Each word felt like swallowing glass.

Patricia’s expression remained neutral as she took notes, but I could see the judgment forming. “Ms. Mitchell, how often did you lock your son in his room during social gatherings?”

“I… I don’t know exactly. Maybe once or twice a month? Whenever I had guests.”

“For how long at a time?”

“Two to four hours, usually.”

“And you provided him with food and water beforehand?”

“Sometimes. Yes. Usually.” The more I talked, the more I realized how thin my justifications sounded. “I just wanted him to be safe. I didn’t want him to accidentally break anything or bother my guests.”

Patricia set down her pen and looked at me directly. “Ms. Mitchell, locking a three-year-old child in a room for extended periods is a form of neglect and confinement. It’s neither safe nor appropriate. Children need supervision, interaction, and care—not isolation.”

“I was just in the next room,” I protested weakly. “I could hear him if he needed something.”

“But he couldn’t reach you, could he? The door was locked. And tonight, when he was thirsty and scared and alone, he took the most accessible liquid he could find, not understanding it was poison.”

The words hit me like physical blows. This was my fault. All of it. Not an accident, not bad luck—my deliberate choices had nearly killed my son.

“What happens now?” I asked.

“Right now, we focus on Oliver’s recovery. But Ms. Mitchell, I need to be honest with you. Child Protective Services will be conducting a full investigation. Depending on their findings and Oliver’s medical outcome, there may be serious consequences, including the possibility of losing custody.”

The room seemed to spin. Losing custody. My son, taken away from me. The thought was unbearable, and yet… hadn’t I already taken myself away from him? Hadn’t I already chosen guests and appearances over his most basic need for a mother’s presence?

Oliver survived, but it was close. He spent three days in the pediatric ICU, his small body fighting the chemical burns in his throat and esophagus. The doctors said he was lucky—if he’d ingested more, or if the ambulance had arrived even five minutes later, he would have died.

I sat by his bedside constantly, holding his hand, watching the monitors, praying to a God I wasn’t sure I believed in to please, please let my baby live.

When he finally woke up, groggy and confused, the first thing he said broke my heart into pieces I’ll never be able to put back together.

“Mommy? Are your friends gone? Can I come out now?”

I collapsed into sobs, pressing my forehead against his small hand. “Yes, baby. Yes, they’re gone. And you never, ever have to go back in that room again. I’m so sorry. I’m so, so sorry.”

But sorry wasn’t enough. Sorry didn’t erase the months of isolation. Sorry didn’t undo the fear and loneliness he’d experienced while I laughed with people I barely cared about.

The CPS investigation was thorough and damning. They interviewed Oliver’s daycare teachers, who reported that he’d become increasingly withdrawn. They talked to my neighbors, one of whom admitted she’d sometimes heard a child crying in my house during my social gatherings but had assumed it was just normal toddler behavior.

They reviewed my social media, which painted a picture of a woman who seemed to have a perfect life—dinner parties, professional success, beautiful home—with very few photos of her son.

The investigator, a stern woman named Ms. Peterson, laid out her findings in a conference room at the hospital.

“Ms. Mitchell, based on our investigation, we’ve determined that Oliver was subjected to regular confinement, isolation, and neglect. While we acknowledge that you provided him with basic necessities like food and shelter, you failed to provide adequate supervision and emotional support. The incident with the cleaning product was a direct result of this pattern of neglect.”

“I never meant to hurt him,” I whispered. “I just wanted to have a normal life. To have friends, to advance my career, to not always have to choose between being a mother and being a person.”

Ms. Peterson’s expression softened slightly. “Ms. Mitchell, I understand that single parenthood is challenging. But being a mother doesn’t mean you can’t have a social life or professional ambitions. It means finding appropriate ways to balance those things—hiring a babysitter, having playdates, including your child in age-appropriate social activities, or simply choosing not to host events when you can’t provide proper childcare.”

“I know that now. I know I made terrible choices. Please, don’t take him away from me. I’ll do anything. I’ll go to parenting classes, therapy, whatever it takes. Just let me keep my son.”

The decision came two weeks later. Oliver was released from the hospital with a long recovery ahead—potential long-term damage to his esophagus, ongoing monitoring for complications, and likely years of therapy to address the psychological trauma.

I was allowed to keep custody, but under strict conditions: mandatory parenting classes, weekly home visits from a social worker, psychological evaluation, and most importantly, no unsupervised contact with Oliver for the first three months. My mother would move in temporarily to ensure Oliver’s safety and proper care.

Additionally, I was required to attend therapy to address the underlying issues that had led to my choices—the obsession with appearances, the inability to ask for help, the prioritization of external validation over my child’s wellbeing.

The court order was humiliating, but it was also fair. I had nearly killed my child through neglect. I deserved every consequence.

My mother arrived from Kansas two days after Oliver came home from the hospital. She was a small, fierce woman in her sixties, and the disappointment in her eyes when she looked at me was almost unbearable.

“Sarah Louise Mitchell,” she said, using my full name the way she had when I was a child in trouble, “how could you? How could you lock that baby in a room like he was something to hide?”

“I don’t know, Mom. I don’t know what I was thinking.”

“You weren’t thinking. You were so worried about what other people thought of you that you forgot to think about your own child.”

She was right, of course. In my desperation to appear successful, competent, and put-together, I’d forgotten the one thing that actually mattered—being a good mother to the small human who depended on me completely.

The first few weeks with my mother in the house were painful. She essentially took over Oliver’s care while I watched from the sidelines, only allowed to interact with him under her supervision. It was like being demoted from parent to visitor in my own home.

But slowly, I began to see what I’d been doing wrong.

I watched my mother with Oliver—the way she got down on the floor to play with him, the way she read to him with different voices for each character, the way she incorporated him into her daily activities instead of working around him. When she baked cookies, Oliver stood on a stool beside her, helping measure and mix. When she gardened, he was there with his own small tools, planting flowers.

Most importantly, she talked to him constantly. Not at him, but with him—asking his opinions, listening to his rambling three-year-old stories, treating his thoughts and feelings as valid and important.

“This is what parenting looks like, Sarah,” she told me one evening after putting Oliver to bed. “It’s not about having a perfect house or impressive friends. It’s about showing up every single day for this little person who needs you.”

“But how do you balance it? How do you have your own life and still be present for your child?”

“You don’t balance it like a scale, trying to give equal weight to everything. You prioritize. Your child comes first, always. And you know what? When you actually prioritize correctly, you find that you can still have friends, still have hobbies, still have a career. But those things fit around your child, not the other way around.”

I started attending my court-mandated parenting classes, expecting them to be punitive and judgmental. Instead, they were educational and surprisingly supportive. The instructor, a former CPS worker named Linda, created a safe space where struggling parents could talk honestly about their challenges.

“Parenting is the hardest job in the world,” she told our small group, “and it’s the only job where you get no training before you start. You’re expected to figure it out as you go, often while dealing with your own trauma and issues. But here’s what I want you to understand: asking for help is not weakness. Using resources is not failure. And admitting you’re struggling is not shameful—it’s brave.”

Through these classes, I learned practical skills I should have known already. How to set appropriate boundaries with a toddler. How to redirect behavior instead of isolating a child. How to find affordable childcare for those times when I genuinely needed adult time. How to build a support network instead of trying to do everything alone.

But more importantly, I began to understand the psychological patterns that had led to my choices. My own childhood, where love felt conditional on performance and achievement. My fear of being judged as a “failed” single mother. My belief that my worth was determined by external validation rather than internal values.

My individual therapy sessions with Dr. Matthews were even more revelatory and painful.

“Sarah, I want you to think about something,” she said during one session. “When you locked Oliver in his room, what were you really trying to lock away?”

I sat with the question for a long time. “My fear,” I finally said. “My fear of being seen as incompetent. Of failing. Of being just another struggling single mother who couldn’t handle it all.”

“And what happened when you tried to lock away that fear?”

“I nearly lost everything that actually mattered.”

Dr. Matthews nodded. “Fear is like that. When you try to hide it or lock it away, it doesn’t disappear—it just finds other ways to manifest. Usually in ways that create the very outcome you were trying to avoid.”

She was right. In my desperate attempt to appear competent and in control, I’d created a situation that proved I was neither. I’d been so afraid of judgment that I’d made choices deserving of the worst kind of judgment.

“The path forward,” Dr. Matthews continued, “is learning to sit with discomfort. To be okay with being imperfect, with asking for help, with showing vulnerability. Those things don’t make you weak—they make you human.”

Three months after the incident, my mother returned to Kansas, satisfied that I was capable of caring for Oliver appropriately. The day she left, I felt both grateful for her help and terrified of being alone with the responsibility again.

But this time was different. This time, I had tools and support systems. This time, I understood what mattered.

Oliver and I started our mornings with breakfast together—no phones, no distractions, just talking about his dreams from the night before and what he wanted to do that day. I’d enrolled him in a wonderful preschool program where he could socialize with other children and develop age-appropriate skills.

I’d also joined a single parents’ support group, where I met other mothers and fathers navigating similar challenges. These weren’t people I was trying to impress—they were people who understood the reality of single parenthood, who swapped babysitting duties, who texted each other on hard days with encouragement and practical help.

One evening, about six months after the incident, I was invited to a book club meeting—the same book club that had been meeting at my house the night Oliver almost died. I’d dropped out of the group entirely after that night, too ashamed to face them.

But Jennifer had reached out personally, saying they’d love for me to rejoin if I felt ready. “We miss you, Sarah. And we want you to know that you don’t have to be perfect. We’re all just trying to figure life out.”

I almost declined. The thought of facing those people again, of them knowing what I’d done, was mortifying. But then I thought about what Dr. Matthews had said about sitting with discomfort.

“I’ll come,” I told Jennifer. “But I need to ask you something. Can I bring Oliver? I have a babysitter I trust now, but I’d actually like to try including him in more of my social activities, when it’s appropriate. He’s gotten really good at playing quietly with his toys, and he loves being around people.”

There was a pause on the other end of the line. Then Jennifer said, “Of course you can bring him. That would be wonderful. The book we’re reading this month is actually about parenthood, so it’s very fitting.”

The night of the book club, I arrived with Oliver holding my hand, carrying his backpack full of quiet toys and books. I’d talked to him beforehand about how grown-ups would be having a discussion, but he could sit nearby and play, and we’d take breaks for him to show everyone what he was working on.

When we walked in, I saw the other women exchange glances. I knew what they were thinking—they knew about the incident. They knew what kind of mother I’d been.

But instead of judgment, I saw something else in their eyes. Compassion. Understanding. Relief that Oliver was okay.

“Hi Oliver,” Jennifer said, kneeling down to his level. “I’m so glad you could come. I have some special cookies I made just for you. Would you like one?”

Oliver looked up at me for permission. I nodded, smiling. “That sounds great, doesn’t it? What do you say?”

“Thank you,” Oliver said softly, taking the cookie.

We settled into the living room, Oliver on a blanket nearby with his toys, me on the couch with the other women. The book discussion was good, touching on themes of parental guilt and redemption that felt painfully relevant.

About halfway through, Oliver came over and tugged on my sleeve. “Mommy, can I show everyone my dinosaur?”

In the past, I would have shushed him, told him not to interrupt. But I’d learned something important: children aren’t interruptions to life. They are life.

“Of course, sweetie. Ladies, Oliver would like to show us something. Is that okay?”

Everyone nodded enthusiastically, and Oliver proudly displayed his toy stegosaurus, explaining in great detail about its plates and how it ate plants and wasn’t scary like the T-Rex.

The women listened attentively, asking questions, and I felt something shift inside me. This—this was what belonging actually looked like. Not a perfectly curated image, but messy, real human connection that made space for all parts of who I was, including being a mother.

After Oliver went back to his toys, Mark (who’d also joined the group that night) said something I’ll never forget: “Sarah, thank you for bringing him. It means a lot that you trust us enough to include him. And… I want you to know that we don’t judge you for what happened. We’ve all made mistakes as parents. Some of us just got luckier with the consequences.”

I felt tears prick my eyes. “Thank you. That means more than you know.”

Two years have passed since the night I nearly lost Oliver. He’s five now, thriving in kindergarten, showing no obvious lasting physical effects from the chemical burns, though he’ll need monitoring for years to come.

The psychological effects are harder to measure. He’s in play therapy to work through the trauma of those locked-door experiences, and some days are harder than others. He still sometimes asks, in a small voice, “Mommy, I’m not in trouble, right? I don’t have to go in my room?”

Each time, I kneel down and look him in the eyes. “No, sweetheart. You’re not in trouble. And I will never lock you in your room again. That was Mommy’s mistake, not yours. You didn’t do anything wrong.”

I’m still in therapy myself, working through the layers of issues that led to my choices. Dr. Matthews says I’ve made remarkable progress, but she also reminds me that healing isn’t linear. Some days I feel confident and capable. Other days I’m overwhelmed by guilt and shame, replaying that terrible night over and over.

My career has changed significantly. I stepped back from the aggressive networking and client-chasing that had consumed me, instead choosing to work from home as a freelance consultant. It pays less, but it gives me the flexibility to prioritize Oliver’s needs—to pick him up from school, attend his class performances, be fully present in his daily life.

I’ve also become an advocate, speaking at parenting classes and support groups about my experience. It’s uncomfortable, exposing my worst moments to strangers. But if my story prevents even one parent from making similar choices, it’s worth the discomfort.

“I thought being a good mother meant having it all together,” I tell these groups. “I thought it meant showing the world that I could manage everything perfectly. But I was so focused on the image I was projecting that I forgot to actually be present for my child. And I nearly lost him because of it.”

The responses I get are varied. Some people are judgmental—I see it in their faces, the thought that they would never do something so terrible. I don’t blame them for that reaction. Before it happened to me, I would have thought the same thing.

But others see themselves in my story. They see the moments when they’ve prioritized appearances over presence, when they’ve hidden their struggles instead of asking for help, when they’ve made choices based on fear rather than love.

One woman approached me after a talk, tears in her eyes. “I’ve been leaving my six-year-old alone in the house for short periods while I run errands,” she confessed. “I tell myself it’s only twenty minutes, that he’s old enough, that he’ll be fine. But listening to your story… I realize I’m just scared of being judged for bringing him with me. I’m going to stop. Thank you for being brave enough to share.”

These moments make the shame worthwhile. If my terrible mistake can prevent other children from suffering, then perhaps something good can come from the worst period of my life.

Last month, Oliver and I had a conversation I’d been dreading. He’s getting older, starting to remember more, and I knew the questions would eventually come.

We were making dinner together—something we do every night now, him standing on his step-stool beside me, helping however he can—when he asked, “Mommy, why did you used to lock me in my room?”

My hand stilled on the knife I was using to chop vegetables. We’d talked about this with his therapist present, but never just the two of us.

I put down the knife and lifted him off the step-stool, sitting on the floor so we were at eye level. “Oliver, that’s a really good question, and you deserve an honest answer.”

He looked at me with his father’s eyes, waiting.

“When you were little—younger than you are now—Mommy made some really bad choices. I was afraid of what people would think of me. I wanted my friends to see me as someone who had everything together, and I worried that if they saw you being a normal three-year-old—sometimes messy, sometimes loud, sometimes accidentally breaking things—they would think I was a bad mom.”

“But that doesn’t make sense,” Oliver said with the clear logic of a five-year-old. “You were being a bad mom by locking me in there.”

The truth of his words hit me like a physical blow. “You’re absolutely right. I thought I was protecting my reputation, but instead I was hurting you. And that night when you got sick from the cleaner—that was my fault. Because you were locked in, alone and thirsty, and you didn’t know that bottle wasn’t safe to drink.”

“I remember that,” he said quietly. “It hurt really bad.”

“I know, baby. I’m so, so sorry. You should never have been in that situation. A good mommy would have had you with her, or would have had a babysitter watching you, or would have just not had friends over that night. There were so many better choices I could have made, and I didn’t make them. That was wrong.”

“But you’re a good mommy now,” Oliver said, touching my face with his small hand. “You don’t lock the door anymore.”

I pulled him into a tight hug, tears streaming down my face. “Thank you for saying that, sweetheart. I’m trying to be a good mommy now. Every single day, I’m trying. But I need you to know something really important—what happened back then was never your fault. Never. You were just a little boy who needed his mommy, and I failed you. That was my mistake, not yours.”

We sat on the kitchen floor together for a long time, me holding him, both of us processing in our own ways. Finally, he pulled back and looked at me seriously.

“Mommy, can I ask you something else?”

“Always.”

“Are you still scared of what people think?”

The question was so perceptive it took my breath away. “Sometimes,” I admitted. “Old fears don’t just disappear completely. But now when I feel that fear, I do something different. I remind myself that the only opinion that really matters is yours—whether you feel loved and safe. And I talk to Dr. Matthews about it. And I ask for help from people who care about us.”

“Like Grandma?”

“Yes, like Grandma. And like Miss Jennifer from book club, and the other mommies in my group, and your teachers. I learned that asking for help isn’t bad—it’s actually really smart.”

Oliver seemed satisfied with this answer. He climbed back onto his step-stool and resumed helping me with dinner, chattering about something that happened at school. The conversation was over for him, processed and filed away.

But for me, it was another step in a journey that would last the rest of my life—the journey of learning to live with what I’d done and to become the mother Oliver deserved.

Six months ago, something unexpected happened that tested everything I’d learned.

I was offered a significant promotion at work—a return to the kind of high-level consulting that had consumed me before the incident. Better pay, more prestige, more opportunities for networking and career advancement.

The old Sarah would have jumped at it immediately, seeing only the external validation and status it represented.

But I was different now. So I did something I never would have done before—I talked it through with my support system. With Dr. Matthews. With my mother. With my single-parent group. And most importantly, with Oliver.

“Sweetie, Mommy got offered a new job opportunity,” I explained one evening. “It would mean more money, which could be good. We could afford that trip to Disneyland you’ve been wanting. But it would also mean Mommy working more hours and being home less. I want to know what you think.”

Oliver thought about it seriously, his five-year-old face scrunched in concentration. “Would you still make dinner with me?”

“That’s a good question. Probably not every night. Maybe three or four nights a week instead of every night.”

“Would you still read stories at bedtime?”

“Yes, always. That’s non-negotiable.”

“Would you still come to my school programs?”

“I would try to, but I might miss more of them than I do now.”

He was quiet for a moment. “Mommy, I don’t need to go to Disneyland. I like when you’re home.”

His words settled something inside me. I turned down the promotion.

My former colleagues thought I was crazy. “You’re putting your career on hold for a five-year-old’s feelings?” one of them asked, genuinely baffled.

“No,” I corrected. “I’m prioritizing my child’s wellbeing over external measures of success. There’s a difference.”

Dr. Matthews was proud of me. “A few years ago, you would have taken that job and convinced yourself you were doing it for Oliver’s benefit. The fact that you consulted him and then honored his feelings shows tremendous growth.”

“I won’t lie,” I told her. “Part of me still feels like I’m missing out. Like I’m choosing to be less successful.”

“Success is subjective, Sarah. You’re successful at the thing that matters most—being present for your son. The corporate ladder will always be there. Oliver’s childhood won’t be.”

She was right. And I was learning, slowly, that true success isn’t measured by job titles or social status or how impressed strangers are with your life. It’s measured by quieter, more intimate metrics—like whether your child feels safe, loved, and valued. Like whether you can look yourself in the mirror and recognize the person staring back.

Today is Oliver’s sixth birthday. We’re having a party at our house—something I never would have risked in the past, terrified of the chaos and mess and potential for things to go wrong.

The house is full of children from his kindergarten class, running around, playing games, making noise, spilling juice, tracking muddy footprints across my floors. It’s controlled chaos, and it’s wonderful.

My mother is here, helping supervise. So are several members of my single-parent support group and their kids. Jennifer from book club came with her family. Even Patricia Rodriguez, the social worker who investigated my case, stopped by with a gift—we’ve stayed in touch over the years, and she’s become an unlikely friend.

Oliver is radiant, wearing his favorite superhero shirt, his face covered in chocolate frosting from the cake. He’s showing his friends his room—that same room where I used to lock him—now filled with artwork they did together, photos of his friends, a calendar where we mark special events together.

There’s no lock on the door anymore. I had it removed the day he came home from the hospital, replaced with a simple latch he can open himself. The message was clear: this is your space, but you’re never trapped here. You’re free to be part of our family, part of our life, always.

As I watch him blow out his candles, surrounded by people who genuinely care about him, I feel something I haven’t felt in years—peace. Not the false peace of a carefully curated image, but the real peace that comes from living authentically, with all your flaws visible, working every day to be better.

After the party, after the guests have left and the house is quiet again, Oliver and I sit together on the couch, both exhausted. He’s clutching his new toys, already half-asleep against my shoulder.

“Mommy,” he murmurs, his voice heavy with sleep. “This was the best birthday ever.”

“I’m so glad, sweetheart. You deserve all the best birthdays.”

“Mommy?”

“Yes?”

“I love you.”

Three simple words that I don’t take for granted anymore. Three words I almost lost the right to hear.

“I love you too, Oliver. More than anything in the whole world.”

As I carry him to bed—to that room that was once his prison but is now his sanctuary—I think about how far we’ve come. About the locked door that nearly destroyed us both, and the open doors we’ve walked through together since then.

I think about the mother I was—so desperate for validation, so afraid of judgment, so disconnected from what actually mattered—and the mother I’m becoming. Imperfect, still learning, still making mistakes sometimes, but present. Finally, fully present.

I tuck Oliver into bed, kiss his forehead, and leave his door open a crack so he can see the light from the hallway. He fell asleep almost instantly, worn out from the excitement of his party, secure in the knowledge that his mother is nearby, available, present.

In the living room, I begin the task of cleaning up—picking up abandoned party hats, sweeping up cake crumbs, wiping chocolate handprints off surfaces. The house is a mess, and I don’t care.

This mess represents something beautiful—life being lived, childhood being celebrated, community being built. The pristine, perfect house I used to maintain was actually empty. This chaotic, messy home is full.

My phone buzzes with a text from Jennifer: Thank you for letting us be part of Oliver’s special day. Watching him blow out those candles surrounded by people who love him… that’s what matters. You’re doing great, Sarah.

I send back a simple heart emoji, feeling grateful for friends who’ve seen me at my worst and still choose to see the best in me.

Later that evening, as I’m finishing the cleanup, I find myself standing in the doorway of Oliver’s room, watching him sleep. I do this sometimes—not obsessively, not constantly, but occasionally, needing to remind myself that he’s here, he’s safe, he’s breathing.

On the wall next to his bed is a framed photo from tonight’s party—Oliver surrounded by his friends, all of them laughing, his face lit up with pure joy. I took that photo and had it printed at the pharmacy on my way home, knowing I wanted him to wake up tomorrow and see it. A reminder that he’s loved, celebrated, important.

Next to that photo is another one—older, more worn. It’s from the hospital, taken the day Oliver was discharged after the incident. In it, I’m holding him, both of us looking exhausted and fragile, but together. I keep that photo there deliberately, a reminder of how close I came to losing him, how precious and fragile this bond is.

My therapist says it’s healthy to remember, as long as the memory serves growth rather than just guilt. So I remember. Every single day, I remember what I almost lost, and I make choices accordingly.

Last week, I was asked to speak at a conference for social workers and child protective services professionals. The topic was “When Parents Change: Success Stories in Family Reunification.”

Standing in front of hundreds of professionals who deal with child welfare cases daily was terrifying. These people knew the statistics—they knew how rarely cases like mine end in true rehabilitation. They knew that most parents who commit the kind of neglect I did either don’t change or change only superficially to regain custody.

But I’d agreed to speak because I wanted them to know that real change is possible, even if it’s rare.

“My name is Sarah Mitchell,” I began, my voice steadier than I felt. “Three years ago, I nearly killed my three-year-old son through neglect. I locked him in his room during social gatherings because I was more concerned with appearing to be a good mother than actually being one. And one night, that choice almost cost him his life.”

I told them the whole story—the locked door, the cleaning solution, the hospital, the investigation, the consequences. I didn’t spare myself any details or make any excuses.

“I share this not because I’m proud of it or because I think I deserve forgiveness,” I continued. “I share it because somewhere in your caseload, there’s probably a parent like I was—someone who’s made terrible choices but who might, possibly, be capable of real change if given the right support and accountability.”

I talked about the interventions that had worked—the mandatory supervision, the parenting classes, the therapy, the support groups. I talked about my mother’s tough love and practical help. I talked about the social workers and therapists who refused to let me make excuses but also refused to give up on me.

“The key,” I said, “was that nobody let me hide from what I’d done. I couldn’t minimize it, couldn’t explain it away, couldn’t pretend it wasn’t that bad. I had to face it fully, sit with the horror of it, and then do the hard work of understanding why I’d made those choices.”

After my talk, several social workers approached me with questions. One of them, a young woman who couldn’t have been more than twenty-five, asked: “Do you ever worry you’ll backslide? That you’ll fall into old patterns?”

“Every single day,” I answered honestly. “That fear is constant. But I’ve learned that fear can be useful if you channel it correctly. My fear of backsliding makes me more vigilant, more committed to my routines and support systems, more willing to ask for help when I’m struggling.”

An older social worker with kind eyes and gray hair asked a different question: “What would you say to parents who are currently where you were three years ago? Parents who are prioritizing their image over their children’s wellbeing but don’t realize how dangerous it is?”

I thought about this carefully. “I would say that if you’re hiding your child from the world—literally or figuratively—you need to ask yourself why. If you’re more concerned with what strangers think than what your child needs, that’s a red flag. And if you’re telling yourself that your child is fine with whatever accommodation or isolation you’ve created, you’re probably lying to yourself. Children are never fine being treated as inconvenient or embarrassing.”

“But,” I added, “I would also say that recognizing you have a problem is the first step. The fact that a parent would feel uncomfortable hearing this message means there’s still self-awareness there, still a chance for change. The parents who are truly unreachable are the ones who feel no discomfort, no doubt, no questioning of their choices.”

That night, I received an email from a woman who’d been in the audience. She wrote:

Dear Sarah,

I attended your talk today, and I need to thank you. I’ve been leaving my four-year-old daughter alone in our apartment for short periods while I work my second job. I’ve told myself it’s necessary, that we need the money, that she’s old enough to be safe for an hour or two. But listening to you describe how you justified your choices, I heard myself. I heard all my rationalizations and excuses.

Tomorrow, I’m going to talk to my social worker about childcare resources I’ve been too proud to ask for. I’m going to stop leaving her alone. Your story may have just saved my daughter from a tragedy. Thank you for being brave enough to share it.

— A mother who’s going to do better

I read that email three times, crying harder with each reading. This was why I put myself through the humiliation of public speaking, the shame of admitting my failures to strangers. If my story could prevent even one child from suffering, it was worth it.

Tonight, as I write this, Oliver is seven years old, thriving in second grade, showing no lasting physical effects from that terrible night. The psychological effects are more subtle—he’s more anxious than other children his age, needs more reassurance, sometimes struggles with trust. We continue therapy, both individually and together, working through the layers of trauma that can’t be rushed or forced.

But he’s also resilient, compassionate, and remarkably well-adjusted considering what he went through. His teachers describe him as kind, thoughtful, always the first to help a classmate who’s struggling. Perhaps his own experience of feeling invisible has made him more attuned to others who might feel the same way.

I’m a different person than I was three years ago. Not perfect—I still struggle with anxiety, still occasionally catch myself worried about others’ opinions, still have moments of doubt and guilt that threaten to overwhelm me.

But I’ve learned to sit with those feelings instead of trying to lock them away. I’ve learned that discomfort is not dangerous, that vulnerability is not weakness, that asking for help is not failure.

Most importantly, I’ve learned that my son is not an inconvenience to be managed or hidden. He’s the most important thing in my life, and his needs—his real, genuine needs for presence, attention, love, and security—come before my comfort, my image, my social life, or my career aspirations.

It’s a lesson that came at a devastating cost, but one I’ll never forget.

Sometimes, on quiet evenings like this, I stand in Oliver’s doorway and watch him sleep, and I’m flooded with gratitude. Gratitude that he survived. Gratitude that he’s still here, that we still have each other, that I was given a second chance I absolutely did not deserve.

And I make promises to that sleeping child—promises I make every single day, promises I intend to keep for the rest of my life:

I will never hide you away again.

I will never make you feel like you’re too much, too inconvenient, too embarrassing to be part of my life.

I will never prioritize what others think of me over what you need from me.

I will show up for you, every single day, in all the messy, imperfect, beautiful ways that real love requires.

And if I ever start to slip back into old patterns, I will catch myself immediately and get help before any harm is done.

Oliver stirs in his sleep, murmuring something about dinosaurs, and I smile. Tomorrow, we’ll wake up and make breakfast together. He’ll tell me about his dreams, and I’ll listen like they’re the most important stories I’ve ever heard. We’ll get ready for school together, him chattering constantly while I braid his sister’s hair—yes, we have a new addition now, a two-year-old daughter named Emma, who will never, ever know what it feels like to be locked behind a door.

And when I drop them at school, I’ll watch them run toward their classrooms, backpacks bouncing, and I’ll feel what I feel every single day now: a mix of joy, gratitude, and bone-deep commitment to being the mother they deserve.

The locked door is gone. The mother who could do that to her child is gone too, replaced by someone harder, softer, more honest, more humble. Someone who understands that the only image worth protecting is the reflection she sees in her children’s eyes when they look at her with trust and love.

This is my story. This is my confession. This is my warning to any parent who might be standing where I once stood, making choices they’ll regret forever.

Your children are not inconvenient. They are not embarrassing. They are not obstacles to the life you wish you had.

They are the life you have. And they deserve a parent who shows up fully, who chooses them over comfort, who loves them more than the approval of strangers.

I learned this lesson the hardest way possible. Please, please learn it an easier way.

The door is open now. It will stay open forever.

That’s my promise, my penance, and my path forward.

THE END

Lila Hart is a dedicated Digital Archivist and Research Specialist with a keen eye for preserving and curating meaningful content. At TheArchivists, she specializes in organizing and managing digital archives, ensuring that valuable stories and historical moments are accessible for generations to come.

Lila earned her degree in History and Archival Studies from the University of Edinburgh, where she cultivated her passion for documenting the past and preserving cultural heritage. Her expertise lies in combining traditional archival techniques with modern digital tools, allowing her to create comprehensive and engaging collections that resonate with audiences worldwide.

At TheArchivists, Lila is known for her meticulous attention to detail and her ability to uncover hidden gems within extensive archives. Her work is praised for its depth, authenticity, and contribution to the preservation of knowledge in the digital age.

Driven by a commitment to preserving stories that matter, Lila is passionate about exploring the intersection of history and technology. Her goal is to ensure that every piece of content she handles reflects the richness of human experiences and remains a source of inspiration for years to come.