The Dumb One

The first time my parents called my daughter “the dumb one,” she thought she’d misheard them.

The second time, she didn’t.

By the third, the word had already lodged itself somewhere deep inside her, like a shard of glass she couldn’t remove. I didn’t know that, not then. All I knew was that on the night of my parents’ 40th anniversary party, in a room full of fifty people I’d known my whole life, my father looked across a sea of champagne flutes and white tablecloths, pointed his smile in the general direction of my child, and casually destroyed her.

“My name is Emma,” she likes to say when she introduces herself. That night, my parents gave her a different name.

The dumb one.

I can still see the ballroom the way it looked when we walked in that Saturday evening. Gold balloons arched over the entrance with big silver numbers—4 and 0—hovering above everyone’s heads like glittering warning signs. A live trio played soft jazz in the corner. Waiters floated through the room with trays of sparkling drinks and tiny hors d’oeuvres that left grease moons on white cocktail napkins.

I had spent an hour curling my hair and another half hour convincing my daughter to wear the pale blue dress we’d bought especially for the occasion. It floated around her knees and made her look younger and older all at once. She’d tugged at the skirt and asked, “Do I look weird?” and I’d cupped her face and told her, “You look perfect.”

That was before the glasses clinked. Before the announcements. Before the word.

Emma took her place at the kids’ table—round, in the far corner, covered with the same linen as the adults’ but already stained with spilled soda and crumbs. She sat on the edge of her chair, shoulders drawn up, hands folded tightly in her lap like she was bracing for something. That’s how she always looked at family gatherings: like she was trying to shrink herself down to something no one could notice or criticize.

Beside her sat my niece, Sophia.

If Emma tries to disappear, Sophia has never once doubted she’s meant to be seen.

Sophia glanced up when we arrived, waved, and launched straight back into an impassioned monologue about a piano piece she was learning. Even from across the room I saw her hands moving in the air, fingers pressing invisible keys. She’s the same age as Emma—twelve—but everything about her is big: her voice, her laugh, the way her achievements seem to arrive like clockwork, one stacked neatly atop the last.

Straight A’s, gifted program, piano prodigy, math competitions, leadership awards. My parents’ golden grandchild.

And then there’s my daughter.

Emma has dyslexia. That’s the short version. The long version is that reading is a battleground for her. Letters swap places; whole words refuse to sit still. She fights with text the way some kids fight with algebra or sports or social cues. Except the world doesn’t pin “dumb” to those other struggles as quickly as it does to reading. My parents never understood that difference. In their minds, difficulty with reading meant difficulty with thinking. And difficulty with thinking meant limited potential.

It’s astonishing how much harm you can compress into a single, lazy assumption.

I remember weaving between tables that night, smiling at relatives I hadn’t seen in months, pretending not to notice the way they angled their bodies toward my sister Rachel the moment she stepped in. Rachel glowed in a form-fitting black dress, her hair sleek and glossy, her laugh bright. People patted her arm and said things like, “How’s our little genius?” and “What’s Sophia won lately?” and “Future Harvard girl, right?”

No one asked Emma anything.

My husband couldn’t make it—an unavoidable work trip—so it was just the two of us. I felt exposed without him. He’s better than I am at deflecting comments with jokes, at sliding between my parents’ barbs and expectations with a smile. Without him there, I felt the weight of the evening pressing down on my shoulders and the skin at the back of my neck prickling in anticipation.

We hadn’t even reached dessert when my mother rose from her seat.

She tapped her champagne glass with the tip of her fork. The chime rang over the heads of our guests, bright and sharp. Conversations tapered off. The trio in the corner softened their playing and then stopped altogether. My mother’s smile turned on, practiced and dazzling.

“We want to thank everyone,” she said, “for celebrating forty beautiful years with us.”

There it was. The performance voice. The one she used at church fundraisers and charity events and, once upon a time, at my school awards ceremonies when Sophia didn’t yet exist and I was still the daughter she boasted about.

“And,” she added, drawing the word out so we could all lean forward together, “we have some exciting news to share.”

I felt my stomach tighten.

I knew this moment was coming. They had told me over the phone three days earlier, in the same tone you use when you mention you’ve booked a table for dinner. We’re planning a big announcement. We’ve finalized our estate planning. That’s how they put it. Finalized. As if there had ever been a draft where Emma’s name weighed the same as Sophia’s.

My father stood up beside my mother. He put his hand over hers and beamed at the room, soaking in the attention. “We’ve been thinking a lot about the future,” he said, “about our legacy and what we want to pass down to the next generation.”

He turned his head toward the kids’ table, toward the two girls picking at their desserts. “And we’ve decided that our granddaughter Sophia”—he paused there for effect—”will inherit the family home and the two hundred and fifty thousand dollar trust fund we’ve established.”

There was a beat of silence, and then the room burst into applause.

People smiled, turned in their chairs, looked at Sophia as if she’d just announced early acceptance to half the Ivy League. Someone near me murmured, “Well deserved,” and another added, “That girl is going places.”

Sophia’s face bloomed into a mixture of pride and embarrassment, the way it always does when she gets attention. She ducked her head, but her eyes shone.

I didn’t hear the rest of the room. For a second everything went muffled, like someone had thrown a thick blanket over the world. All I heard was the pounding of my own heart.

Then I saw Emma.

She was looking down at her plate, her fingers curling into the white linen napkin in her lap. Her small shoulders drew even tighter. Her chin trembled once, twice, the way it had when she was little and trying very hard not to cry in public. Her throat worked like she was swallowing something that hurt going down.

My sister Rachel stood and dabbed at her eyes with a napkin, her voice shaky with practiced emotion. “Mom, Dad, this means so much,” she said. “Sophia will treasure this legacy.”

My mother nodded, smiling through tears that appeared right on cue. “We know she will, darling. We’ve seen how hard she works, how brilliant she is. She’s shown such promise, such real intelligence.” Her eyes swept the room and then, deliberately, landed on Emma.

The way she said intelligence, I knew what was coming before she opened her mouth again.

“We love both our granddaughters, of course,” she said. “But Sophia—well, she’ll do something meaningful with this inheritance. She’ll truly make something of it.”

My blood turned cold.

I could have lived with the unfairness of the money. People show their favorites in a thousand small ways, and I’d known for years where their spotlight fell. But it was the next part that took my breath away.

My father chuckled—actually chuckled—and said, “Emma’s a sweet girl. But let’s be honest, she’s the dumb one. She’ll be fine with a simple life. She doesn’t need this kind of responsibility.”

The dumb one.

He said it like a joke, like a gentle ribbing, like something benign. But there’s nothing harmless about publicly branding a twelve-year-old as stupid. Not when she’s been working twice as hard as anyone realizes just to stay afloat. Not when that word has haunted her in whispers and comparisons for years.

The dumb one.

He could have slapped her and it would have hurt less.

Emma rose so fast her chair tipped backward and clattered to the floor. Heads turned at the noise, but before anyone could fully register what had happened she was gone, slipping between tables, one hand over her mouth, her hair a blur of pale brown as she fled toward the hallway.

I heard a door slam. A second later, a choked sob.

I started to stand, but Rachel’s fingers clamped around my wrist. “Don’t make a scene,” she hissed. “They’re just being practical.”

Practical.

That word hit me almost as hard as dumb. As if reducing my daughter’s inheritance, her worth, her potential, to a fraction of her cousin’s was nothing more than a simple mathematical decision. As if hurt feelings were a small price to pay for financial efficiency.

I pulled my arm free so hard her hand jerked. “I’m already in a scene,” I said, my voice low. Then, instead of turning toward the bathrooms, I walked straight to the front of the room.

If my parents were going to rip my daughter apart in front of fifty people, then fifty people were going to hear the truth about her.

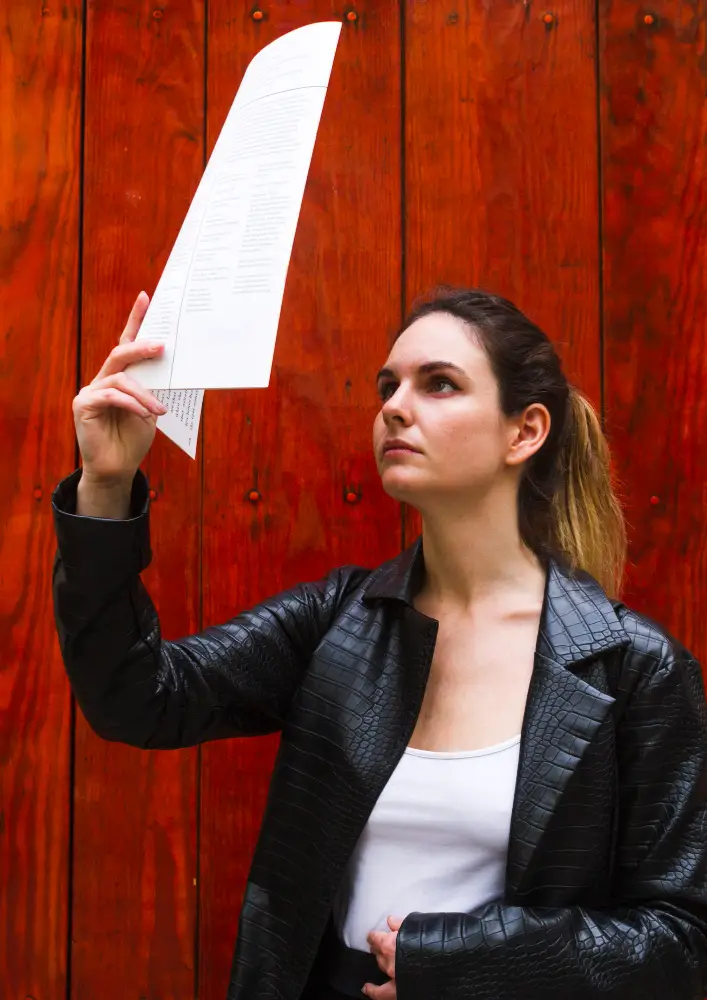

I picked up an empty champagne glass from a nearby table, feeling the cool weight of it against my palm. My heart hammered against my ribs. I took a breath, then lifted the glass and tapped it with my fork. Once, twice, three times. The sound rang out, sharp and clear.

The room quieted. Forks paused midway to mouths. Conversations stuttered and died.

“I have an announcement too,” I said.

My voice surprised me. It was steady, calm, the way it gets when I’m past being hurt and firmly in the territory of anger that has crystallized into something like resolve.

My mother stiffened, her smile flickering. “Victoria,” she began, “this isn’t the time—”

“Oh, I think it’s the perfect time,” I said.

I turned slowly, letting my gaze travel over faces I’d known since childhood: friends of my parents, relatives, family friends who still called me “Vicky” in holiday cards. They looked back at me with polite curiosity and, in some cases, discomfort. No one likes the moment when pleasantries fracture.

“You’ve just announced,” I said, “that my daughter Emma is too dumb to inherit anything. That she’ll live a simple life, that she doesn’t deserve your legacy.”

A hush spread through the room, heavy and thick.

“I want everyone here to know something about Emma,” I continued. “Something my parents clearly don’t.”

I reached into my purse. My fingers brushed against the folded letter I’d slid in there earlier that afternoon, almost as an afterthought. I had originally put it there because I couldn’t bear to leave it at home. It felt too important, too fragile. Now I understood why I’d brought it.

But before we get to that letter, to what I told them and what broke open that night, you need to understand how we got there. How a little girl went from being written off as “the dumb one” to becoming someone MIT wanted to hear from.

Because my parents weren’t always this blunt about their judgment. Once upon a time, the things they said were soft around the edges, dressed up as concern or realism. The cruelty came in layers, thin enough at first that it took me years to realize how heavy they’d become.

Emma was seven when I first sat in a stuffy school conference room and heard the word dyslexia.

I remember the fluorescent lights buzzing faintly overhead, the smell of burnt coffee from a pot that had clearly been sitting too long on a hot plate, the big analog clock ticking just loud enough to make me wish I could rip it from the wall. On one side of the table sat Emma’s teacher, a woman with kind eyes and worry lines etched permanently between her brows. Next to her was the principal, fingers laced together, face arranged in careful neutrality. Beside them, a reading specialist with a stack of test papers and charts.

“Mrs. Nash,” Emma’s teacher began, “thank you so much for coming in.”

When a teacher thanks you for coming in, it’s never for something light.

My palms were already damp. “Is everything okay?” I asked, even though the answer had been hovering in my mind for months. You don’t ask for a meeting with a teacher and a principal and a specialist because everything is fine.

“Emma’s been struggling,” the teacher said gently. “She’s significantly behind in reading compared to where we’d expect her to be at this point.”

“How far behind?” I asked.

The reading specialist slid a paper across the table and tapped a line with her pen. “She’s reading at a first-grade level,” she said. “And she’s in second grade.”

I swallowed. That one grade difference felt enormous, like a canyon between where my daughter was and where she was supposed to be.

“But she’s so bright,” I said automatically. “She’s curious, she loves asking questions, she remembers everything she hears—”

“No one is questioning her intelligence,” the reading specialist said. “In fact, that’s part of why we’re concerned. Emma’s comprehension when things are read aloud to her is excellent. But when she has to decode the words herself, she struggles significantly. We think she should be tested for a learning difference. Specifically, dyslexia.”

The word landed like a pebble in my stomach, small but heavy.

“Dyslexia?” I repeated.

She nodded. “It’s a specific learning disability that affects reading and related language-based processing skills. It doesn’t mean she isn’t smart. It just means her brain processes written language differently.”

Just.

It’s amazing how many complicated realities we try to fit behind that one tiny word.

The tests came a week later. Emma sat in a quiet room answering questions, reading lists of words, trying to sound out nonsense syllables. When she came home that afternoon, she was exhausted, red-eyed, and unusually quiet.

“Was it hard?” I asked, brushing hair from her forehead.

She shrugged and picked at the strap of her backpack. “The letters kept dancing,” she muttered.

The results confirmed what they’d suspected: severe dyslexia.

Letters flipped. Words scrambled. Reading wasn’t just difficult for her; it was an exercise in frustration every single time.

I spent the next month buried in research. I read articles and books and online forums until the words blurred together. I learned about decoding strategies and multi-sensory instruction, about interventions that worked best when started early. I discovered that dyslexia was surprisingly common, that it had nothing to do with how smart a child was, that some of history’s most brilliant minds had struggled to read and spell.

I also discovered how expensive help could be.

I found a specialist who came highly recommended and started Emma in tutoring three times a week. We shuffled our schedules, cut back on eating out, postponed a vacation we’d been planning for years. Emma, bless her, didn’t complain once about the extra work. She sat through those sessions, tracing letters in sand, saying sounds aloud, building words with tiles, reading sentences that made no sense but trained her brain to see patterns. She worked so damn hard.

My parents did not understand.

“She just needs to focus more,” my dad said when I explained the diagnosis to them over dinner one evening. “Back in our day we didn’t have fancy names for everything. Some kids are just slow learners.”

“It’s not about focus,” I insisted. “She has a different way of processing written language. Her brain—”

My mother waved a hand dismissively. “Dys-something,” she said. “It’s just a nice way for doctors to say not smart enough. You’re being too sensitive, Victoria. She’ll catch up if you stop coddling her.”

There it was. That word again. Not smart enough.

They said it casually, like they were commenting on the weather. They had no idea how those words would echo in my daughter’s head years later.

I stopped trying to explain dyslexia to them after that. There are only so many times you can bang your head against a closed door before you realize you’re the one getting hurt, not the wood.

Meanwhile, Sophia was thriving.

From kindergarten onward, she seemed to absorb information through osmosis. She brought home straight A’s without appearing to break a sweat. She read chapter books in first grade, wrote elaborate stories in second, and won spelling bees and math competitions as if winning were simply her baseline state of existence.

Every family dinner turned into a Sophia Appreciation Hour.

“Did you hear she won the district math competition?” my mother would crow. “Her teacher says she’s the smartest student she’s ever had.”

“She’s going to Harvard someday,” my father would add, lifting his wine glass. “Just you wait.”

They said these things in front of Emma. In front of everyone. As if shining a spotlight on one child required turning out the lights on the other.

Emma would sit there quietly, pushing peas around her plate, eyes fixed on the tablecloth as if it contained secrets more deserving of her attention than the conversation.

When she was nine, she came into the kitchen one evening while I was making dinner. The smell of garlic and onions filled the air. The late afternoon sun streaked across the floor in long golden bars. I was stirring a pot of sauce when she leaned against the counter and asked, in a voice that tried very hard to sound casual, “Mom, am I stupid?”

The spoon froze mid-stir. “What?” I turned around. “Of course not. Why would you think that?”

She stared at the floor. “Grandma said I’m not as smart as Sophia. That I’ll never be able to do what she does.”

For a second I couldn’t speak. My chest felt too tight.

“What exactly did she say?” I asked carefully.

Emma’s face crumpled. “She said Sophia has special gifts and I’ll find my own path. A simpler one. She said there’s nothing wrong with simple, but she said it like…like simple is a bad thing.”

I knelt down so I was eye-level with her. “You listen to me,” I said, holding her shoulders. “You are not stupid. Your brain just works differently when it comes to reading. That’s all. You’re funny, you’re kind, you remember everything anyone ever tells you, and you notice things other people miss. That’s not stupidity. That’s a different kind of intelligence.”

She searched my face for a long moment, as if trying to decide whether she could trust what she saw there more than what she’d heard at my parents’ house.

“Then why does Grandma always talk about Sophia?” she whispered. “Like she’s the only one who’s good at stuff.”

I didn’t have a good answer for that. “Because sometimes adults are wrong,” I said finally. “Even when they think they’re right.”

The next day, I drove to my parents’ house, adrenaline buzzing under my skin.

“Did you tell Emma she wasn’t as smart as Sophia?” I demanded as soon as my mother opened the door.

She blinked. “I didn’t say that exactly.”

“What did you say, exactly?”

She sighed, as if I were being unreasonable. “I said Sophia has special gifts. Emma will find her own path. A simpler one. Not everyone is meant for big things, Victoria. I’m being realistic. You should be too. You’re filling that child’s head with unrealistic expectations.”

“She’s nine,” I said, my voice shaking. “You are crushing her confidence.”

“I’m saving her from disappointment,” my mother insisted. “Better she learns now that she’s not—”

“Not what?” I snapped. “Not worth investing in? Not worth believing in?”

My mother straightened, offended. “Don’t put words in my mouth.”

I realized then that I could not make my parents see what they didn’t want to see. They had already written Emma’s story in their heads. In that story, she was a background character: sweet, simple, destined for a small life. Anything that didn’t fit that narrative slid right off their perception.

But Emma had other plans.

Tutoring helped. Slowly, painfully, reading shifted from outright torture to something merely very difficult. Her progress was measured in inches, not miles, but those inches were hard-won. By the time she reached fifth grade, she was reading at grade level. She still had to work twice as hard as her classmates, but she did it. She did it.

Along the way, she discovered something that lit her up in a way nothing academic had before: science.

It started with a documentary about ocean pollution. She watched it one rainy Saturday afternoon, curled up on the couch with a blanket and a bowl of popcorn. By the time the credits rolled, she was sitting upright, eyes wide.

“There’s so much trash in the water,” she said, horrified. “Why doesn’t everyone fix it?”

If reading was a slog, listening was effortless. She devoured audiobooks about conservation, watched documentaries on climate change, clicked through article after article about water quality and environmental disasters. She filled a notebook with messy, cramped handwriting—facts, figures, questions, little sketches of ideas. She’d bring me pages and say things like, “Did you know some people don’t have clean water to drink?” or “Why don’t we build more filters like this one?”

One afternoon, about a year before the anniversary party, she came home from school practically vibrating with excitement.

“Mom, I want to build something,” she said, dropping her backpack by the door and rifling through its pockets until she pulled out a wrinkled flyer. “A water filter. For people who don’t have clean water.”

I took the flyer and smoothed it out. National Youth Science Competition, the header read. Ages 12-18. Cash prizes. Mentorship opportunities. The rest of the page was filled with details about project guidelines and submission deadlines.

“Is this for a school project?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “It’s a real competition. For kids all over the country. I want to enter.”

“The competition is for kids up to eighteen,” I said slowly. “You’ll be on the younger side.”

“I know.” She puffed air nervously from her nose. “But I’ve been reading about water filtration and I have ideas. I can do it, Mom. I know I can.”

She said it with a steadiness that made something inside me straighten.

“Okay,” I said. “Let’s do it.”

We cleared out a corner of the garage. The lawnmower and boxes of old Christmas decorations were shoved to one side. In their place, we set up a folding table, a whiteboard, and a collection of supplies Emma insisted she needed: sand, gravel, activated charcoal, plastic bottles from the recycling bin, PVC pipes.

For six months, the garage became part science lab, part disaster zone. There were nights I stepped over puddles and scattered tools just to get to the laundry. I watched Emma hunched over her makeshift workbench, goggles slipping down her nose, hair escaping from a messy bun, muttering to herself as she poured water through yet another prototype.

Sometimes it worked. More often it didn’t.

We tested each iteration with simple kits: drops that changed color based on contaminant levels, cheap digital meters ordered online. When a design failed, Emma wrote down what went wrong, circled it, and said, “Okay, so that didn’t work. What if I try…?” And then she tried again.

Failure didn’t seem to scare her the way reading tests once had. Maybe it was because, for the first time, she was failing on her own terms, in pursuit of something she cared about deeply.

One evening, I found her sitting on the garage floor surrounded by crumpled papers and half-assembled contraptions, frustration radiating from every line of her body.

“It’s not good enough,” she said when I sat beside her. “It filters some stuff, but not enough. I’m never going to get this right.”

“You’re trying to solve a problem people with advanced degrees work on,” I reminded her gently. “The fact that your filter works at all is impressive.”

She crossed her arms. “Impressive isn’t good enough.”

I smiled. “You sound like your grandparents.”

She made a face. “Ew. Take it back.”

In the end, she built a filtration system that used sand, gravel, activated charcoal, and recycled plastic bottles stacked in a specific configuration she’d tweaked over dozens of attempts. It wasn’t fancy. It didn’t look like something out of a sleek lab. But it removed 98% of contaminants in our test water.

Ninety-eight percent.

We triple-checked the numbers, then quadruple-checked them. When we were sure, she wrote up her process in painstaking detail—dictating most of it to me while I typed, because asking her to write that many pages by hand would have been an act of cruelty. She took photographs, drew diagrams, and packaged it all together for submission.

I didn’t tell my parents.

I couldn’t bear to hear, “That’s nice, honey, but did you see Sophia’s latest piano trophy?”

Two months later, an email landed in my inbox from the competition organizers. I opened it while stirring soup, glancing at the screen with half my attention. A second later, the spoon slipped from my hand and clanged against the pot.

“What?” Emma asked, looking up from her homework at the table.

“You—” My voice came out strangled. I cleared my throat and tried again. “Emma, you placed third.”

She blinked. “Third in my age group?”

“Third overall,” I said. “Nationwide. Out of five thousand entries.”

For a moment she just stared at me. Then her eyes filled with tears. “Are you serious?”

“Completely serious.” I grabbed her and spun her around the kitchen. We were both laughing and crying at the same time. It felt like our little house couldn’t possibly contain all the pride and joy swelling inside me.

We celebrated that night with ice cream and a movie on the couch. She fell asleep halfway through, head on my shoulder, fingers still sticky from melted chocolate.

I thought briefly about calling my parents. The words formed in my mind—Emma placed third in a national science competition—but I could already hear their response. That’s nice. Did you hear Sophia was invited to play at the state-level recital? The thought soured the taste in my mouth. I decided not to tell them. Letting them ignore her achievements felt safer than giving them more ammunition to twist into backhanded compliments.

Around the same time, Emma started writing poetry.

It began as little notes in the margins of her science notebook: fragments of lines, images of rivers and plastic bottles and fish caught in nets. Her tutor noticed first.

“Victoria,” she said one afternoon while Emma was in the bathroom. “Emma has a real gift for language. Not in the conventional sense, maybe, but in the way she puts ideas together. Have you seen her writing?”

I frowned. “Her writing is usually…messy.”

“I don’t mean her handwriting,” the tutor said, smiling. “I mean the way she thinks in metaphors. She sees the world differently. It comes through in her words. You should encourage it.”

That night I bought Emma a journal. A simple one with a blue cover and thick paper that wouldn’t bleed through. I left it on her pillow with a note: For your thoughts, poems, ideas, and anything else living in that brilliant brain of yours.

She filled that journal in two months. Then another. And another.

Some of her poems were about nature—a river trying to carry away sadness, a forest that remembered every footstep. Some were about feeling different, about letters that refused to behave, about teachers who saw more than test scores and grandparents who saw less. One day she asked, “Do you think anyone would ever want to read these? Like…real people, not just you?”

“I think your poems are amazing,” I said honestly. “I don’t know what ‘real people’ means, but I know there are magazines that publish kids’ writing. We could send a few in. Just to see what happens.”

Her eyes lit up. “Really?”

We selected three poems and submitted them to a youth literary magazine online. I tried to manage her expectations, telling her that even grown-up writers got rejected all the time. She nodded, but I could see hope glimmering under her attempt at nonchalance.

Three weeks later, an email arrived: We’re delighted to accept…

I screamed. She screamed. We danced around the kitchen again. A few months after that, two more poems were accepted by another magazine.

At twelve years old, Emma had three published poems and a national science award.

Still, my parents knew none of this.

Then, one ordinary Tuesday, Emma came home from school with an envelope.

“Mom, this came for me today,” she said, holding it out. It was thick, high-quality paper with a logo in the corner: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

My brain stuttered. “Where did you get this?”

“They handed it to me in the office,” she said. “They said it came in the mail.”

Hands trembling, I opened the envelope and unfolded the letter.

Dear Emma Nash,

We are excited to inform you…

My eyes skimmed the lines, then slowed, then went back to the top. MIT was launching a new summer program for gifted young scientists. Ages twelve to fifteen. They had seen Emma’s project from the National Youth Science Competition. They were impressed. They were inviting her to apply for a spot in their inaugural cohort.

I looked up at her, stunned. “Emma, do you know what this means?”

She shifted her weight. “Is it…good?”

“Good?” I laughed, half-hysterical. “MIT is one of the best science schools in the world. They don’t just send letters like this for fun. They noticed you. They want you to apply.”

She took the letter from my hands, eyes scanning slowly. Her lips moved as she read, sounding out the words under her breath the way she always did with dense text. Then she whispered, almost to herself, “But I’m the dumb one. Grandpa said so.”

Something inside me broke.

“You are not dumb,” I said fiercely. “You never were.”

“Then why does everyone think I am?” she asked, and there was no anger in her voice, just tired confusion.

“Because they don’t understand dyslexia,” I said. “They see you struggling with reading and they think it means you’re not smart. They don’t see how hard you work. They don’t see the way your brain lights up when you talk about water filtration. They don’t know about your poems or your competition or this letter. That’s on them, not on you.”

She looked at the letter again. “Do you think I could get into the program?” she asked.

“I think you can do anything you set your mind to,” I said. And for once, it didn’t feel like a platitude. It felt like a simple statement of fact.

We filled out the application that night. She wrote essays—again dictating most of the words while I typed, because I refused to let her dyslexia turn a doorway into a wall. She described her project, her love for environmental science, her curiosity. She talked about dyslexia too, about how it forced her to break problems down differently. We hit submit the next day.

Two days later, my parents called.

“Victoria,” my mother said, voice bright, “we’re planning our anniversary party. Forty years. Can you believe it?”

I made a noise somewhere between a laugh and a sigh.

“We want to make a big announcement,” she continued, “about our estate planning. We’ve decided who will be inheriting the house and the trust fund. It will be a beautiful moment. Very meaningful.”

My stomach dropped. “What kind of announcement?”

“Well, Sophia’s been doing so well,” my mother said. “Straight A’s, piano, leadership roles at school. We’ve decided to leave the family home and the two hundred and fifty thousand dollar trust fund to her.”

I gripped the phone tighter. “And Emma?”

“We’ll leave her some money, of course,” my mother said. “Maybe twenty thousand. Enough to help her get started in whatever simple career she chooses.”

Twenty thousand versus two hundred and fifty thousand. One child as the primary heir to the “legacy,” the other tossed a consolation prize. My throat burned.

“Mom,” I said slowly, “Emma is not—”

“We’ve made our decision,” she interrupted. “It’s what’s fair.”

Fair. They misused that word as effortlessly as they misused dumb.

After we hung up, I sat at the kitchen table staring at the wall until the sunset outside turned everything orange.

I almost didn’t go to the party. I almost told them to enjoy their celebration without us, to give their speech without my daughter sitting in the corner absorbing every word like poison. But something inside me refused. It felt wrong to absent Emma from a story about her, even if that story was cruel. It also felt wrong to let that story be the only one.

So we went. She wore her blue dress. She plaited her hair herself, hands clumsy but determined.

“Are you okay going tonight?” I asked as we drove. The city lights blurred past her window.

She shrugged. “I don’t really want to see Grandma and Grandpa,” she admitted. “But I want to see Sophia.”

I appreciated her honesty. “If at any point you want to leave, you tell me,” I said. “We’ll go, no questions asked.”

“Even if it’s in the middle of the party?” she asked, a small smile tugging at her mouth.

“Especially then,” I said.

Back in that ballroom, after my father’s speech and Emma’s flight to the bathroom, I stood holding a champagne glass, the weight of years pressing against my ribs.

“I have an announcement too,” I’d said to the room. Fifty faces turned toward me.

I pulled my phone from my purse first. On the screen was a photo of Emma standing beside her homemade filtration system, goggles on, grin huge, shoulders squared with quiet pride. I held it up.

“Last year,” I said, “Emma entered the National Youth Science Competition. On her own, she researched, designed, and built a water filtration system that removes ninety-eight percent of contaminants using recycled materials. Out of five thousand entries nationwide, she placed third.”

A murmur rippled through the crowd. My parents’ faces went pale.

“She also writes poetry,” I continued, swiping to screenshots of digital magazines. “Beautiful poetry. Three of her poems have already been published in literary magazines. At twelve years old.”

I turned to face my sister. “Sophia is talented. No one is denying that. She works hard, and she deserves every bit of praise she gets. But Emma is not dumb. She is dyslexic. There is a difference.”

My mother opened her mouth, eyes watery. “We didn’t know—”

“You didn’t know because you never asked,” I said. “You never looked past your idea of who she is. You just labeled her and moved on.”

Finally, I pulled out the folded letter that had been burning a hole in my purse all evening. The MIT letter.

“And last week,” I said, my voice suddenly thick, “Emma received this.”

I held it up.

“This is from MIT, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,” I said, in case anyone in the room somehow hadn’t heard of it. “They saw her science project and were impressed enough to invite her to apply to their new summer program for gifted young scientists. The program is for kids ages twelve to fifteen. My daughter is the youngest age eligible, and they want to see more from her.”

Gasps. Whispers. A few people exchanged looks that clearly said, We had no idea.

“Emma is not the dumb one,” I said. “She has dyslexia, which means reading is hard. It means she has to work twice as hard as other kids just to read a page of text. But she does it. And beyond that, she’s curious and creative and determined. That is what intelligence looks like. That is what you’ve refused to see.”

I met my parents’ eyes. My father looked like someone had punched him. My mother was openly crying now, mascara smudging beneath her eyes.

“We’re sorry,” she whispered. “We didn’t understand.”

“You didn’t want to,” I replied. “It was easier to compare her to Sophia, to pick a favorite, to write Emma off as destined for a ‘simple’ life.”

Rachel shot to her feet, her chair scraping loudly. “Victoria, this isn’t the time for this,” she snapped. “You’re ruining their party.”

“When is the time?” I asked. “After you’ve collected your inheritance? After Emma spends her entire childhood thinking she’s worthless because the people who are supposed to love her unconditionally decided she wasn’t worth investing in?”

No one answered.

I took a breath, feeling my hands shake. “Keep your trust fund,” I told my parents. “Keep your house. Emma doesn’t need it.”

My father frowned. “Don’t be ridiculous,” he said. “This is for Emma’s future.”

“She’s going to build her own future,” I said. “With or without your money. What she needed—what she still needs—is your respect. Your belief in her. And you have failed her in that more than any inheritance could ever fix.”

I set the champagne glass down. The clink against the table sounded final.

Then I walked away.

Down the hallway, I found the bathroom door closed. I knocked gently. “Emma? It’s Mom.”

There was a muffled sniffle. “Go away.”

“I will if you want me to,” I said, leaning my forehead against the door. “But I just told everyone the truth about you. About your science project. About your poems. About MIT.”

Silence. Then the sound of the lock turning.

The door opened a crack and one red-rimmed eye appeared. “You told them?” she asked, voice small.

“I told them,” I said. “I told them everything. And then I told them to keep their money.”

She opened the door wider. “You what?”

“I’ll explain in the car,” I said softly. “If you’re ready to go.”

She nodded. Tears still streaked her cheeks, but there was a spark in her eyes that had not been there when she ran away from the table.

We walked back through the ballroom. The music had started up again, but it felt wrong, too cheerful for the air now filled with tension and hushed conversations. My parents called after us. My father’s voice trembled. “Victoria, please. Let’s talk about this.”

I didn’t turn around.

We stepped out into the cool night air. My hands shook as I fumbled with the keys, but once we were in the car and the doors were closed, a strange quiet settled over us.

“Mom,” Emma said after a few minutes of driving, her voice tentative. “Did you mean all that stuff? About me being smart?”

I pulled the car over to the side of the road and put it in park. Then I turned to her fully.

“Every single word,” I said. “Emma, you are brilliant. Not because of MIT or competitions or publications. Those things are wonderful, but they’re just reflections of something that’s already there. You’re brilliant because of the way you think, the way you care, the way you keep going even when things are hard.”

She looked unconvinced. “But I have dyslexia,” she said. “I can’t read like other kids.”

“Dyslexia doesn’t make you dumb,” I said. “Some of the smartest people in history had dyslexia. Albert Einstein. Thomas Edison. Steven Spielberg. They struggled with words on a page, but that didn’t stop them from changing the world.”

She stared out the window for a moment. Then she said quietly, “I got into the MIT program.”

For a second I thought I’d misheard. “What?”

“The email came this morning,” she said, turning back to me. Her eyes were bright now, almost glowing. “I didn’t want to tell you until after the party. I thought maybe it could be good news if…if tonight was bad. I got in, Mom. They want me.”

All the air rushed out of my lungs. “You—you got in?” I stammered. “And you were just going to sit through that dinner with that secret in your pocket?”

She shrugged. “I wasn’t sure. I still thought maybe I didn’t deserve it. Because, you know…dumb one.”

A sound came out of me that was half laugh, half sob. I unbuckled my seatbelt, leaned across the console, and wrapped my arms around her.

“I am so, so proud of you,” I whispered into her hair. “I don’t care what my parents think. I don’t care about their party or their money. You did this. You earned this. MIT wants you, and so do a thousand problems in the world that need your brain.”

She hugged me back, tightly. We stayed like that for a long time while the car’s hazard lights blinked in the darkness like a slow, steady heartbeat.

In the days that followed, my parents called. A lot.

I ignored every ring. My voicemail filled with messages.

“Victoria, please, we need to talk.”

“You overreacted.”

“We didn’t mean it that way.”

“Of course we’re proud of Emma.”

“We’ve rethought everything. Call us back.”

I didn’t.

A week later, they showed up at my house.

Emma was at school when the doorbell rang. I nearly didn’t open the door, but curiosity won out over the urge to pretend I wasn’t home.

My parents stood on the porch looking older than I’d ever seen them. My mother’s makeup was minimal, eyes puffy. My father’s shoulders were slightly slumped, as if someone had deflated him.

“May we come in?” he asked.

For a long moment I considered saying no. Then I stepped aside.

We sat at the kitchen table—the same table where Emma and I had celebrated her victories, where she’d written poems and filled out applications. It felt like neutral ground and home turf all at once.

“We’re so sorry,” my mother began, her voice breaking. “We had no idea Emma was so…accomplished.”

“You would have known,” I said, “if you’d paid attention. If you’d asked about her instead of using her as a measuring stick to make Sophia look taller.”

My father winced. He took an envelope from his jacket and slid it across the table toward me. “We’ve revised our estate plan,” he said. “We’re splitting everything equally between the girls now. The house, the trust fund, all of it. That’s what’s fair.”

I didn’t even open the envelope. I pushed it back toward him.

“Emma doesn’t want it,” I said.

My mother’s mouth fell open. “What? Don’t be ridiculous. Of course she does.”

“She doesn’t need your money,” I said. “She needs your respect. Your love. Your belief in her. You can’t buy back the years you spent calling her slow, implying she was destined for less. That damage won’t vanish because you adjusted some numbers in a lawyer’s office.”

“How do we fix this?” my mother whispered. Her voice held something I hadn’t heard directed at me in a long time: genuine humility.

I sighed. I’d had a week to cool down, but some anger still simmered. Underneath it, though, was something else: a reluctant hope. Not for my sake. For Emma’s.

“Start by learning what dyslexia actually is,” I said. “Read about it. Not in order to argue or minimize, but to understand. Go to a workshop. Talk to a specialist. Stop treating it like a synonym for stupidity.”

My father nodded slowly. “We can do that,” he said.

“And then,” I continued, “apologize to Emma. Really apologize. No excuses. No ‘we didn’t mean it that way.’ Tell her you were wrong. Tell her she is brilliant. And then accept that she may not forgive you quickly. Rebuilding trust will take years, not weeks. You don’t get to rush her because you’re uncomfortable with the consequences of your own actions.”

My mother wiped her eyes. “We’ll do anything,” she said. “We…I don’t want to lose my granddaughter.”

“That’s not up to you anymore,” I said softly. “That’s up to her.”

They left the envelope on the table even after I tried to hand it back a second time. I eventually put it in a drawer. Not as a backup plan for Emma, but as a reminder that some things cannot be fixed with money.

Over the next several months, my parents did something I never thought they would: they changed.

They bought books about dyslexia. Real books, written by experts and adults who’d grown up with it. They attended workshops and listened to teachers and specialists explain how different brains process language in different ways. My mother called me one afternoon, voice small, and said, “I had no idea that many brilliant people struggled with reading. I thought it meant…well, I thought wrong about everything.”

My father went further. He volunteered at a literacy center that specialized in helping kids with learning differences. He came home from his first session looking shaken. “There was a boy there,” he told me over coffee one Saturday morning. “Nine years old. Bright as anything. He can solve complex math problems in his head, but he can’t read the word ‘cat’ without struggling. And his parents…they look at him the way I looked at Emma.”

He paused, staring into his mug. “I never want to be that person again.”

It wasn’t easy. There were moments when old habits surfaced, when they’d start to compare or dismiss. But now, when it happened, they caught themselves. They apologized. They tried again.

One evening, about three months after the party, they asked if they could take Emma to dinner. Just the three of them.

Emma looked at me, uncertain. “Do I have to?”

“You don’t have to do anything,” I said. “But I think they’re trying. Really trying. It’s up to you whether you want to give them the chance.”

She thought about it for a long time. Finally, she said, “Okay. But if they say anything mean, I’m leaving.”

“Fair enough,” I said.

They took her to her favorite restaurant, the one with the big windows overlooking the river. When she came home two hours later, she was quiet. Not sad, exactly. More thoughtful.

“How was it?” I asked.

She set her purse down and sat at the kitchen table. “Grandpa cried,” she said.

I blinked. “Your grandfather? Cried?”

She nodded. “He told me he was sorry. He said he didn’t understand dyslexia and he said things that weren’t true and weren’t fair. He said he was proud of me. That he’s been reading about water filtration and he thinks what I’m doing is important.”

“What did you say?” I asked gently.

She shrugged. “I said thank you. I didn’t know what else to say.”

“That’s okay,” I said. “You don’t have to know yet.”

“Grandma asked if she could come to the first day of my MIT program,” Emma added. “She wants to see the campus. She said she wants to understand what I’m learning.”

I felt something loosen in my chest. “What did you tell her?”

“I said maybe,” Emma said. “I’m not ready to say yes. But I’m not ready to say no forever either.”

“That’s more than fair,” I said.

Emma looked at me, her eyes serious. “Do you think people can really change? Like, actually change, not just pretend?”

“I think it’s hard,” I said honestly. “I think it takes work and time and a willingness to admit you were wrong. But yes, I think people can change. Whether they do or not is up to them.”

She nodded slowly. “I want to believe they’re trying. I just…I don’t want to be hurt again.”

“You don’t have to rush,” I said. “You get to set the pace. You get to decide what you’re comfortable with. And if they mess up—because they probably will, at least a little—you get to decide whether that’s something you can work through or not.”

“Okay,” she said. Then, after a pause, “Mom?”

“Yeah?”

“Thank you for standing up for me. At the party. I know that was hard.”

I reached across the table and took her hand. “Emma, you are my daughter. Standing up for you will never be hard. It’s the easiest thing I’ve ever done.”

Right now, as I write this, Emma is halfway through her first year at MIT’s summer program.

She’s thriving.

Every week, I get updates that make my heart swell. She’s working on advanced filtration techniques with actual MIT professors. She’s collaborating with kids from across the country who share her passion for solving environmental problems. She’s presenting her ideas in front of university faculty and holding her own.

And yes, she still struggles with reading. Some nights she calls me frustrated because an assignment required reading a fifty-page research paper and it took her four hours to get through it while her roommate finished in ninety minutes. On those nights, I remind her that the roommate might read faster, but Emma notices things in the text that others miss. She sees connections, patterns, implications that come from having to work so deliberately through every word.

“Different doesn’t mean deficient,” I tell her. “It means you’re looking at the same information through a different lens. Sometimes that lens catches things others don’t see.”

Last month, she gave a presentation about accessible water purification systems for communities in developing countries. She proposed a design that could be built using locally available materials and maintained without specialized training. At the end of her presentation, one of the MIT faculty members stood up and said, “This is the kind of thinking we need in environmental engineering. You’re not just solving a technical problem. You’re solving a human problem.”

Emma called me that night and cried. Happy tears this time.

“He said I was solving a human problem, Mom,” she said, her voice catching. “Not just a technical one. Do you know what that means?”

“Tell me,” I said.

“It means I’m thinking about the people. Not just the science. It means the way my brain works—the way I have to break everything down and think about it differently because of dyslexia—it’s actually helping me see solutions other people might miss.”

I closed my eyes, grateful she couldn’t see the tears streaming down my face. “That’s exactly what I’ve been telling you,” I said. “Your brain is extraordinary precisely because it works differently.”

“I think I’m starting to believe you,” she whispered.

My parents did come to campus on Family Day, about a month into Emma’s program.

I was anxious about it. So was Emma. But they showed up with genuine curiosity instead of judgment. They toured the labs, asked Emma thoughtful questions about her work, and listened—really listened—to her explanations about filtration rates and contamination testing.

At one point, my father pulled me aside while Emma was showing my mother her project workspace.

“I need you to know something,” he said. His voice was rough. “I failed her. For years, I failed her. I let my own ignorance and my own narrow idea of what intelligence looks like rob me of seeing who she really is.”

I didn’t say anything. I just waited.

“I can’t get those years back,” he continued. “I can’t undo the damage. But I’m going to spend the rest of my life making sure she knows I see her now. The real her. The brilliant, determined, creative person she’s always been.”

“She needs to hear that from you,” I said. “Not me.”

He nodded. “I’m working on it. I’m not good at this. I’m not good at admitting when I’m wrong. But I’m trying.”

“Keep trying,” I said. “That’s all any of us can do.”

Before they left that day, my mother took both of Emma’s hands in hers.

“I’m so proud of you,” she said, and her voice shook. “Not because you’re at MIT. Not because you won competitions. I’m proud of you because of who you are. Because you kept going even when I made you feel like you weren’t worth it. You proved me wrong, and I will be grateful for that for the rest of my life.”

Emma’s eyes filled with tears. “Thank you, Grandma,” she whispered.

It wasn’t forgiveness. Not yet. But it was a beginning.

Three months ago, something remarkable happened.

Emma’s work caught the attention of a professor who specializes in sustainable engineering. He reached out and asked if she’d be interested in co-authoring a paper with him about low-cost water filtration systems for underserved communities.

A twelve-year-old, co-authoring an academic paper.

She said yes.

The process has been grueling. She’s had to read dense technical journals, synthesize complex information, and contribute her own ideas to a professional document. Her dyslexia makes every step harder than it would be for someone else. But she’s doing it.

Last week, she sent me a draft of one section she’d written. I sat in my kitchen reading her words—clear, precise, full of insight—and I thought about the seven-year-old who once asked me if she was stupid.

I thought about the nine-year-old who asked why her grandparents didn’t think she was good at anything.

I thought about the twelve-year-old who fled a ballroom in tears because someone called her “the dumb one” in front of fifty people.

And then I thought about the young woman she’s becoming: fierce, brilliant, undeterred by obstacles, determined to make the world better.

That little girl in the blue dress didn’t need her grandparents’ inheritance. She didn’t need their validation or their money or their vision of what her life should look like.

What she needed was someone to believe in her. To see past the label. To recognize that different doesn’t mean less.

She needed someone to tell her the truth: that she was never the dumb one.

She was always extraordinary.

The paper is scheduled to be published next spring. Emma will be thirteen by then—the youngest co-author the journal has ever had.

When I told my parents, my mother cried. Not performative tears this time, but real, messy, overwhelming emotion.

“I almost destroyed her,” she said. “If you hadn’t stood up for her that night…”

“But I did,” I said. “And she survived. More than survived. She’s thriving.”

“Because of you,” my father said.

“No,” I corrected. “Because of her. I just made sure she had the space and support to become who she already was.”

Last week, Emma came home for a long weekend. She sprawled on the couch with her journal and a pen, scribbling poetry between answering my questions about her classes.

“Mom,” she said suddenly, looking up. “Do you remember when Grandpa called me the dumb one?”

My whole body tensed. “Yes,” I said carefully.

“I’ve been thinking about that night a lot,” she said. “About how much it hurt. But also about what happened after.”

“What about it?” I asked.

She set down her journal. “You could have just told me he was wrong. You could have comforted me and taken me home and let that be the end of it. But you didn’t. You made sure everyone knew the truth. You made them see me.”

“You deserved to be seen,” I said.

“I know that now,” she said. “But I didn’t know it then. And if you hadn’t done what you did that night, I might never have learned it. I might have spent my whole life believing I was less than. That I wasn’t worth investing in. That my brain was broken.”

She paused, her eyes bright. “So thank you. For loving me enough to make them look. For believing in me even when I didn’t believe in myself.”

I crossed the room and pulled her into a hug. “You never have to thank me for that,” I said. “Loving you is the easiest thing I’ve ever done.”

She laughed, the sound muffled against my shoulder. “Even when I left puddles all over the garage and ruined your organized recycling system?”

“Even then,” I said. “Especially then.”

We stood there for a long moment, mother and daughter, surrounded by the life we’d built together out of hard work and hope and stubborn refusal to let anyone else define who we were.

“I’m going to keep going,” Emma said when we finally pulled apart. “With the water filters. With the writing. With everything. I’m going to prove that different doesn’t mean deficient.”

“You already have,” I said.

She smiled. “Then I guess I’ll just keep proving it. Over and over. Until everyone knows.”

“The world is lucky to have you,” I said.

“I’m lucky to have you,” she replied.

And in that moment, standing in our little kitchen with the evening sun slanting through the windows and my daughter’s journal open on the counter and the future spreading out before us like an unmapped country full of possibility, I knew something with absolute certainty:

No amount of money could ever measure a person’s worth.

No inheritance could ever replace belief.

No trust fund could ever matter more than trust itself.

Emma didn’t need her grandparents’ legacy. She was too busy building her own.

And that legacy—the one she was creating through grit and brilliance and an unshakeable determination to make the world better—would far outlast any house or bank account or family name.

My daughter was never the dumb one.

She was always the extraordinary one.

The one who saw problems others ignored and imagined solutions others couldn’t.

The one who turned her so-called limitation into a lens that helped her see the world more clearly.

The one who proved that intelligence isn’t about how fast you read or how easily words come to you.

It’s about how you think. How you care. How you refuse to give up even when every letter on the page seems determined to defeat you.

Emma taught me that.

And now, she’s teaching the world.

One filtration system at a time.

One poem at a time.

One moment of brilliant, defiant, beautiful difference at a time.

THE END

Lila Hart is a dedicated Digital Archivist and Research Specialist with a keen eye for preserving and curating meaningful content. At TheArchivists, she specializes in organizing and managing digital archives, ensuring that valuable stories and historical moments are accessible for generations to come.

Lila earned her degree in History and Archival Studies from the University of Edinburgh, where she cultivated her passion for documenting the past and preserving cultural heritage. Her expertise lies in combining traditional archival techniques with modern digital tools, allowing her to create comprehensive and engaging collections that resonate with audiences worldwide.

At TheArchivists, Lila is known for her meticulous attention to detail and her ability to uncover hidden gems within extensive archives. Her work is praised for its depth, authenticity, and contribution to the preservation of knowledge in the digital age.

Driven by a commitment to preserving stories that matter, Lila is passionate about exploring the intersection of history and technology. Her goal is to ensure that every piece of content she handles reflects the richness of human experiences and remains a source of inspiration for years to come.